Bach 300: The year 1723 and its repercussions

“a new epoch in his creative life”

For obvious reasons, anniversary celebrations usually look back to the year of a composer’s birth or death. From our perspective, however, Johann Sebastian Bach’s 300th birthday in 1985 now lies several decades in the past, while the memory of the 250th anniversary of his death in the year 2000 is also starting to fade. And we still have quite a few years to wait before embarking on the 350th birthday celebrations in 2035. The only notable recent milestones have been connected to three outstanding instrumental works from Bach’s time in Cöthen (all of which were dated by the master himself), namely the 300th anniversaries of the Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (1720), the Brandenburg Concertos (1721) and the Well-Tempered Clavier (1722). In 2023, however, we remember a very special event that was to represent a turning point in Bach’s creative and compositional work.

Since 1985, Bach’s lifespan from 1685 to 1750 has run in step with our own age at an interval of precisely 300 years, creating an ideal framework to trace in detail his musical development as expressed through individual works. In 2023 comes a major turning point when we commemorate the beginning of Bach’s work as cantor at Leipzig’s Thomaskirche in the spring of 1723. This not only marked a new epoch in his creative life, which lasted a full 27 years, but also heralded his single most productive phase. This is especially true of the vocal music and, in particular, the cycles of cantatas written largely in the early years at Leipzig.

Thomaskirche, Leipzig

It is worth remembering that about a hundred years ago, the significance of Bach’s arrival at the cantorate could not be as carefully appraised as it is today. For it is due to the labor of modern scholars that, for the first time, we largely understand the history and sequential ordering of the vocal works composed in Leipzig. Most importantly, the cantatas can now be assigned to one of several annual cycles. Thus, especially for the first Leipzig years of 1723–1725, it is now possible to draw up an essentially complete calendar for the 300-year anniversaries.

Bach’s inaugural work as Thomascantor was the cantata “Die Elenden sollen essen” BWV 75 (“All the starving shall be nourished”, Carus 31.075) for the 1st Sunday after Trinity on 30 May 1723. Two days later he officially began his duties. Three months earlier, on Quinquagesima Sunday, 7 February 1723, the hopeful candidate had successfully passed the preliminary audition for the cantorate with a performance of the two cantatas “Jesus nahm zu sich die Zwölfe” BWV 22 (“Jesus calling then the Twelve to him”, Carus 31.022) and “Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn” BWV 23 (“Thou very God and David’s Son”, Carus 31.023). Bach quickly became the favorite to succeed the previous Thomascantor Johann Kuhnau, who had died in 1722 after holding the post for 21 years (and previously serving as organist at the Thomaskirche).

J. S. Bach

Du wahrer Gott und Davids Sohn

(Thou very God and David’s Son – 3rd version)

Carus 31.023

Bach’s regular Leipzig cantata cycles began with the 1st Sunday after Trinity, which was the start of the school year, continuing each Sunday while also marking the feast days of the Virgin Mary, the Apostles, and the Reformation, as well as the three holidays of Christmas, Easter and Pentecost. Reviewing the demanding Leipzig performance calendar of the 1720s at a distance of three centuries, we are astounded by the ceaseless industry of the Thomascantor, who produced new scores week after week. The numbers of vocal works written in the first calendar years speak for themselves: 39 (1723), 56 (1724), 40 (1725) and 44 (1726–1727).

It should be noted that in his first year as cantor, Bach occasionally lightened a heavy workload by resorting to cantatas he had brought with him from Weimar. For example, for the 3rd Sunday after Trinity in 1723, he selected the cantata “Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis” BWV 21 (“Lord my God, my heart and soul were sore distressed”, Carus 31.021), composed in 1714. In many such cases, however, he still had to rearrange or rework these Weimar cantatas to reflect the performance conditions in Leipzig. In a further effort to make use of older works, he turned secular cantatas written during his time in Cöthen into sacred parodies by introducing new texts. Examples here are the cantatas BWV 66 (Carus 31.066), 134 (Carus 31.134), 173 (Carus 31.173) and 184 (Carus 31.184) for the minor feasts of the second and third days of Easter and Pentecost in 1724.

J. S. Bach

Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis

(Lord my God, my heart and soul were sore distressed – 1st version)

Carus 31.021

The data clearly shows a marked decline in productivity – apparently according to plan – from mid-1725 onward. It seems that Bach had decided relatively early to abandon the practice of writing short-lived cantatas to be heard only once, instead creating a solid repertoire of pieces. To this end, he built up a body of work in his early years as Thomascantor from which he could then draw time and again. This notion of a repertoire of cantatas is a clear departure from the approach of contemporaries such as Christoph Graupner and Georg Philipp Telemann, who left behind vast oeuvres of more than 1,400 and 1,750 cantatas respectively, or Gottfried Heinrich Stölzel, who wrote at least 12 cantata year-cycles. Bach was truly pioneering in his efforts to shape the still young genre, developing it into the singular artwork we still cherish today. In this respect, the corpus of cantatas he created may be easily considered to eclipse all similar bodies of work.

The Leipzig cantatas are all of a uniformly high standard. Moreover, works such as “Herr, gehe nicht ins Gericht mit deinem Knecht” BWV 105 (“Lord, be not too quick to judge”, Carus 31.105), “Schauet doch und sehet, ob irgendein Schmerz sei” BWV 46 (“Look ye then and see now”, Carus 31.046), “Es ist nichts Gesundes an meinem Leibe” BWV 25 (“There is naught of soundness within my body”, Carus 31.025) or “Warum betrübst du dich, mein Herz” BWV 138 (“What is it troubles thee, my heart”, Carus 31.138) – to pick only four examples from Cycle I of 1723–1724 – illustrate the diversity of musical form and marvelous expressive depth of Bach’s vocal works.

This is even more true of Cycle II, which consists entirely of new works, thus making the school year 1724/25 the most prolific of Bach’s life. Beginning with “O Ewigkeit, du Donnerwort” BWV 20 (“Eternity, thou thundrous word”, Carus 31.020), the Thomascantor composed an uninterrupted series of 44 choral cantatas, based exclusively on chorale melodies and texts. For unknown reasons, this carefully laid-out cycle came to an abrupt end with “Wie schön leuchtet der Morgenstern” BWV 1 (“How beauteous is the morning star”,Carus 31.001), written for the Feast of the Annunciation on 25 March 1725.

After Easter 1725, Bach returned to the standard form of mixed cantatas based around Biblical texts, chorale verses and other poetic elements – a format he maintained in later church years. But here, too, we often encounter surprising musical innovations such as the inclusion of extended concertante movements to open a work, also at times featuring (especially from 1726) obbligato organ. Finally, the ambitious cantata project begun in 1723 essentially came to an end around 1729. Bach later composed only a handful of new cantatas, although he did take the opportunity to revise and improve older works when drawing on his cycles for church performances.

The arrival of Bach in Leipzig in 1723 not only launched his great period of cantata writing, but also provided an impetus to compose music for the High Feast days. The 5-part Latin Magnificat BWV 243 (Carus 31.243), which the Thomascantor conceived for the Christmas Vespers service in 1723, was his first large-scale vocal work. This was followed by the St. John Passion “Herr, unser Herrscher” BWV 245 (Carus 31.245) for Good Friday Vespers in 1724, which he performed again the following year in a heavily revised version featuring the opening chorus “O Mensch bewein dein Sünde groß”. While the 300th anniversaries of these vocal works are just around the corner, we still have to wait some years before celebrating the creation of the St. Matthew Passion BWV 244 (Carus 31.244): Only fragments of the first version of this work from 1727 are available to us, and it was not in fact until 1736 that “the great Passion” (as it was known in the Bach family) received the final form we know today. The brilliant oratorical trilogy of works for Christmas, Easter and Ascension were also written in the 1730s.

Despite the profusion of vocal music composed in 1723 and the years immediately following, we should not forget that the Thomascantor remained true to his old habits. Alongside his church duties, he continued to write new works for organ and piano as well as chamber and orchestral music. Unfortunately, it is impossible to date these instrumental pieces as precisely as the vocal works, which are so obviously tied to the church year. But perhaps this simply reminds us that while anniversaries serve to highlight various aspects of Johann Sebastian Bach’s oeuvre, the survival and impact of his music is quite independent of any such ephemeral celebration.

J. S. Bach

Magnificat in D major

Carus 31.243

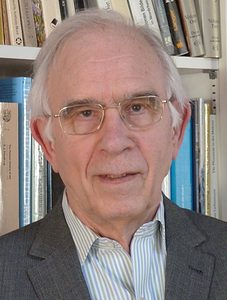

Prof. Dr. Dr. h.c. Christoph Wolff is one of the most distinguished Bach researchers of our time. He is professor emeritus at Harvard University and was director of the Leipzig Bach Archive from 2001 to 2013.

(c) Martin Förster

(c) Martin Förster (c) Heinz Bunse - https://www.flickr.com/photos/buffo400/33658694355 cc by-sa-2.0

(c) Heinz Bunse - https://www.flickr.com/photos/buffo400/33658694355 cc by-sa-2.0

Bach’s first composition in Leipzig in May 1723 probably was the brief, concise Pentecost Cantata 59 (Neumesiter IV libretto, 1714), May 16, 1723, at the Paulinerkirche, the Leipzig University church. It uses the Gospel dictum as the opening chorus, “He who loves me, he will my word keep,” (Wer mich liebet, der wird mein Wort halten), John 14: 23-31, the Promise of the Spirit. This final Last Supper Farewell Discourse to the Disciples also is found in Bach’s first Pentecost Cantata 172 (Weimar, 1714), No. 2, bass secco recitative and arioso (probably Salomo Franck libretto). Source: https://bach-cantatas.com/LCY/M&C-Pentecost.htm.

Thank you very much for your message. BWV 59 was definitely performed in 1724, but there is no record of a performance in May 1723. Bach was not yet in Leipzig on 16 May 1723. We are using the new Bach catalogue of works from 2022 as a guide.