The “astonishing pathways” of Albert Lortzing

The “world champion of Spieloper” also composed a sacred anthem

Albert Lortzing: Hymne

“Dich preist, Allmächtiger”

LoWV 5, 1822

Carus 23.005/00

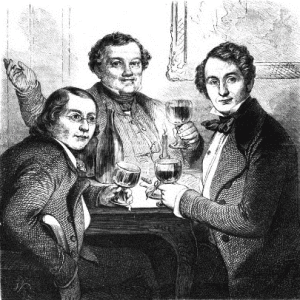

Albert Lortzing in Leipzig with two friends

from: Die Gartenlaube Nr. 41 (1864)

Author and poet Carl Herloßsohn (1804-1849), resident in Leipzig from the late 1820s;

and “Bassbuffo” Gotthelf Leberecht Berthold (1796-1851), resident in Leipzig from 1832

Our editor Barbara Großmann gives an overview of Lortzing’s life and work.

“A brilliant man of the theater”, “the inventor of the so-called German Spieloper”: these are the terms one inevitably comes across when searching for information on Albert Lortzing, for example on the website of the Albert Lortzing Society. The English site albertlortzing.org even calls him a “jack-of-all-trades in theater and opera”.

It stands to reason that a “jack-of-all-trades” will sometimes follow “astonishing pathways”. And biographer Jürgen Lodemann notes that this is true of Albert Lortzing.[1] The subtitle of his book runs: “The life and work of the beloved poet, composer and singer, paterfamilias and world champion of comic-tragic Spieloper from Berlin” – practically a concise biography in itself. One would not really expect sacred music to feature in the biography of the composer of Zar und Zimmermann or Der Waffenschmied and “world champion of Spieloper”. Yet the verse-writing, composing, and singing jack-of-all-trades did in fact write two “serious” sacred works: an oratorio entitled Die Himmelfahrt Jesu Christ in 1828 and – one of his earliest surviving compositions – a sacred anthem from 1822 to a text by poet Friedrich von Matthisson (1761-1831), who was highly esteemed by Friedrich Schiller.

In 1822, when he composed the hymn in Elberfeld, Lortzing was, together with his parents, still a member of Joseph Derossi’s so-called “ABC Theater Society”, which performed regularly in the cities of Aachen, Bonn, Cologne, Düsseldorf and Elberfeld (in alphabetical order). The 21-year-old, who was already something of a ladies’ man, usually played (and sang) the role of the young lover. At the time he was already engaged to fellow troupe member Rosine Regina Ahles, whom he married in 1824. “Without my family, I am only half a man, incapable of anything,” Lortzing once wrote to a friend.[2] Later, this only surviving child would himself have a large family of eleven to look after (although several of his brood died young).

Until the age of twelve, Albert Lortzing grew up in Berlin. There, as a five-year-old, he witnessed Napoleon enter the city after defeating the Prussian forces at Jena and Auerstedt; in the German capital, he took down the famous quadriga from the Brandenburg Gate, sending it to Paris along with other spoils of war. The French occupation and the political unrest of those years ruined the hide business of Lortzing’s parents, after which they upped sticks in 1812 and turned their hobby – acting – into a profession. Restless, often difficult years of travel followed: to Breslau, Bamberg, Coburg, Strasbourg, Baden-Baden, and Freiburg. Under these unpropitious circumstances, the young Lortzing could no longer enjoy regular music lessons as in Berlin, even though his parents did their utmost to encourage their son. He soon appeared in children’s roles, recited poems during performance intervals and helped supplement the family’s meager income by copying sheet music.

In his Autobiographical Sketch, Lortzing himself says: “Even as a boy, I had a great love of music and wrote my own compositions.”[3] Among other works, he set Friedrich Schiller’s “Die Bürgschaft” as a teenager and wrote a “dramatic legend” on August von Kotzebue’s “Der Schutzgeist”. Unfortunately, none of these youthful works have survived. Instead, we have a poem by the eight-year-old, which he dedicated to his parents on New Year’s Day, 1810:[4]

Ein guter Sohn und artger Knabe

erfüllt mit Freuden seine Pflicht

drum bring ich heut zur Morgengabe

ein freundliches Neujahrs:Gedicht

Ich weih es meiner Eltern Liebe,

die sorgsam wachet für mein Glück,

und wünsche gern aus reinem Triebe

mit Dankbarkeit im frohen Blick:

…

Travel is an education in itself. The constant moving in his youth and the many different people he met in those politically turbulent years certainly gave Lortzing many valuable experiences which later helped him become the “world champion of Spieloper”. He often had the opportunity to attend large concerts, such as at the Rhenish Music Festival, where it is possible that he heard great choral-symphonic works such as Handel’s Messiah or Haydn’s Creation. The latter’s influence can certainly be detected in the Hymne of 1822: the thematic approach is similar to that of Haydn’s oratorio, in particular the celebration of the universe and its Creator:

Dich preist, Allmächtiger,

der Sterne Jubelklang.

Dich preist, Allgütiger,

der Seraphim Gesang.

Die ganze Schöpfung schwebt

in ewgen Harmonien,

so weit sich Welten drehn

und Sonnenheere glühn.

This first of three verses provides the framework for the composition and is repeated at the end. Lortzing subsequently inserted a short instrumental “Introduzione” at the beginning. Characteristic of his operas, and already evident in this early sacred anthem, is the small-scale instrumentation.[5] For Lortzing, changes in vocal and instrumental scoring are an important way of giving expression to the text – much more than harmonic finesse. Individual instruments or groups of instruments are added to the string parts, often for just a few bars or for a short motif, such as the majestic and striking brass interjections and timpani rolls in “Dich preist, Allmächtiger” or the gentle clarinet motif used as a contrasting element in “der Sterne Jubelklang”.

The second verse of the Hymne on the beauties of the Creation is more intimate in character. Performed by solo tenor, the accompaniment is for the most part only strings and woodwinds. The third verse on the lowliness and finiteness of human existence and our faith in God’s mercy is extraordinary in its reduced scoring down to four-part voices a cappella, but especially in the strongly rhythmic and subtly underlaid pianissimo text passage “Es trennt vom Totenkreuz mich nur ein Spannenraum”. Three soloists with string and woodwind accompaniment express the comforting belief in resurrection before the return of the powerful opening verse.

Lortzing’s experiences and ambitions in the field of opera are evident in the strongly contrasting dynamics – not least due to the varied scoring – as well as in his memorable, often delightful, melodic invention. But he also knows how to make effective use of polyphony, such as in the fugal entries of the soloist ensemble on the text “So weit sich Welten drehn”. Incidentally, only the solo tenor can be called a “true” solo part: soprano, alto and bass solo always appear in ensemble. Good choral singers thus have the perfect opportunity to test their skills.

If fate had enabled Lortzing to abandon his life as an itinerant singer-actor, maybe he would have received a sound musical training; and then, just maybe, this “jack-of-all-trades” would have written more sacred music. The desire to turn his attention to “serious” music was always there. Perhaps we would have seen the “world champion of Spieloper” take even more astonishing pathways. He certainly had the potential.

[1] Jürgen Lodemann, Lortzing, Göttingen 2000, p. 56.

[2] Quote from Walter Dietrichkeit, Gustav Albert Lortzing, Bad Pyrmont 2000, p. 32.

[3] Quote from Irmlind Capelle. Chronologisch-thematisches Verzeichnis der Werke von Albert Lortzing (LoWV), Köln 1994, p. 15.

[4] Taken from Lodemann, p. 32f.

[5] See also Ursula Kramer: “‘Die Stimme der Natur’ oder: Auf den Spuren von Lortzings musikalischem Tonfall”, in: Lortzing und Leipzig. Musikleben zwischen Öffentlichkeit, Bürgerlichkeit und Privatheit, edited by Thomas Schipperges, Hildesheim 2014, pp. 315-336.

George Frideric Handel: Messiah

HWV 56, 1742

Carus 55.056/00

Joseph Haydn: The Creation

Oratorio

Hob. XXI:2, 1798

Carus 51.990/00

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!