See with your ears and listen with your eyes

For Hans-Christoph Rademann the motet “Ich bin ein rechter Weinstock” from Geistliche Chor-Music 1648 is one of the most beautiful compositions by Heinrich Schütz. This motet teaches you how to see with your ears and listen with your eyes in a way that hardly any other musical piece can…

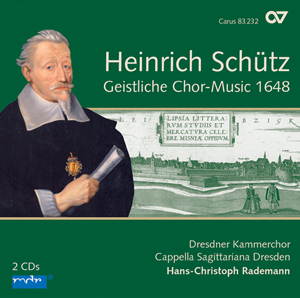

Under the overall musical direction of Hans-Christoph Rademann, the Dresdner Kammerchor and Carus have concluded the first Heinrich Schütz Complete Recording. This month sees the release of the last CD in the Complete Recording.

In my opinion, the motet “Ich bin ein rechter Weinstock” from Geistliche Chor-Music 1648 is one of the most beautiful compositions by Heinrich Schütz. This motet teaches you how to see with your ears and listen with your eyes in a way that hardly any other musical piece can. I sang this composition with the Dresdner Kreuzchor as a ten-year-old boy and had encountered it time and again by the time I was 18. It touched me deeply every time, but I didn’t know why. There had to be a secret to it. Later on, I frequently came across the text on its own, and the familiar music would immediately begin to sound deep within me. I find this internal music, triggered by words, very fascinating.

One day, this ‘secret’ finally revealed itself to me: in Radebeul, near Dresden, I was able to enjoy the view of a vineyard behind my house every day – and suddenly, I saw the music by Heinrich Schütz in the landscape! I perceived the terrace and the small terrace steps in a different way, and I recognized the structures of music in this image. Here, I saw the deeply familiar motet “Ich bin ein rechter Weinstock”.

Schütz writes a vineyard into the score, with terrace-shaped melodic lines and interspersed little motif units as descending steps. And he composes vines with series of eighth notes that surround the pitches. A section of the middle part, where the text reads “wird er reinigen”, is composed in triple time. “ER”, signifying the trinity, is symbolized by the number 3. In general, numerical symbolism plays an important role: two voices sing in the beginning, interpreting Christ, who says: “Ich und der Vater sind eins” (“I and the father are one”, John 10:30), but is still separated from God. Christ represents the number two of the trinity. The text passage “also auch ihr nicht, ihr bleibet denn in mir” culminates in grandeur: here, Schütz shapes the music into a body of dense voice leading.

Personally, I consider these multifaceted levels of meaning in Heinrich Schütz’s scores to be a real treasure. They explain to me what music is and what it is capable of expressing. I have therefore created an internal treasure chest for myself in which many great works of music form a reservoir I can draw on. But at the very top lies the motet “Ich bin ein rechter Weinstock”, which I would love to conduct over and over again, as it always emerges with the same freshness and novelty as the first time I encountered it with the Dresdner Kreuzchor.

Hans-Christoph Rademann is one of the most sought-after choir conductors and renowned choral sound specialists in the world. His concerts and recordings with the Dresdner Kammerchor and the Dresdner Barockorchester are pioneering, especially those of Central German musical treasures from the 17th and 18th centuries. Under the leadership of Musical Director Hans-Christoph Rademann, the Dresdner Kammerchor released the first complete recording of Heinrich Schütz’s works together with the publisher Carus-Verlag Stuttgart.

When it comes to paying tribute to Heinrich Schütz’s compositional achievement, in his art his treatment of the text and language must be mentioned first. The “Geistliche Chor-Music 1648”, a collection of 29 motets for five to seven voices and one of his most important works, is characterized by he carefully thought-out musical realization of the meaning of the text. In his detailed foreword to the collection the composer presented these as models for composition without a basso continuo – it was his conviction that very young composer should obtain “the properfoundation for a good counterpoint.”

When it comes to paying tribute to Heinrich Schütz’s compositional achievement, in his art his treatment of the text and language must be mentioned first. The “Geistliche Chor-Music 1648”, a collection of 29 motets for five to seven voices and one of his most important works, is characterized by he carefully thought-out musical realization of the meaning of the text. In his detailed foreword to the collection the composer presented these as models for composition without a basso continuo – it was his conviction that very young composer should obtain “the properfoundation for a good counterpoint.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!