“Mendelssohn’s last vocal work, crowning his entire output”

Frieder Bernius on Mendelssohn’s “Elijah”

50 years of Carus – 50 years of passion for choral music, which we share with you. In the Carus anniversary year, each month in the CARUS blog prominent choral directors present their personal highlight from five centuries of choral music for you.

In Germany, Mendelssohn’s Elias (Elijah) only became re-established in the core oratorio repertoire since the 1980s. After his death the work was only occasionally performed there, and performances were banned in the Third Reich.

Since then, what has led to it rapidly becoming one of the most popular oratorios of all, to becoming a pinnacle of choral music? And can the work be called an oratorio when it involves so many dialogues and crowd scenes, dealing simultaneously with natural events and heavenly messengers? In contrast to his hero Handel, Mendelssohn had very little experience with operatic subject matter before he turned to oratorio. Throughout his career he searched for an opera libretto, but nothing inspired him to write a setting; he must have had his own ideas about it. But, as a Jew baptised Christian, he felt particularly drawn to an Old Testament subject towards the end of his short life. Was this perhaps because it led him back to his roots?

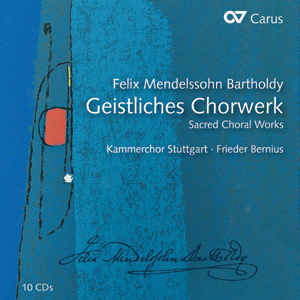

Frieder Bernius is in great demand worldwide as a conductor, seeking a sound which is both authentic and at the same time distinctive and personal – whether in the vocal works of Monteverdi, Bach, Handel, Beethoven, Schütz, or Ligeti, the incidental music of Mendelssohn, or the symphonies of Haydn and Schubert. Bernius has conducted the complete recording of the sacred vocal music of Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy and many other recordings of works by a huge variety of composers, and is also editor of many music editions published by Carus-Verlag.

No, this story does not need the formality of a staged realisation: the music itself allows a scene to be created in our own imagination in such a way that we can be guided by the musical inventiveness alone. Where in oratorio can we find more palpable scenes than those in the Baal choruses; how can we see the prophet travel heavenwards more vividly than at the end of the chorus “Then did Elijah”? Where can you hear the most varied movements of the wind more than in the chorus “Behold, God the Lord passed by”? And where can comfort be better understood than in the invitation in the Angels’ Trio to Elijah, lying on the ground, with its enraptured “Lift thine eyes”? Perhaps the placing of the three Angels in a gallery is possible – a spatial-scenic concession to their invitation to glance upwards, and is thus the exception which confirms the rule.

Mendelssohn: Elijah. An oratorio based on the words of the Old Testament MWV A 25

- Original version: Carus 40.130/00

- Arrangement for chamber orchestra (J. Linckelmann):

Carus 40.130/50

The versatility of the choral writing in Elijah presents a special challenge: how can the same group of singers do justice to the cries for help of the people of Israel, the despairing cries of the priests of Baal, the comforting “Be not afraid” or the christological-ecstatic promise at the end “He shall call upon his name”, so that the sound of each of these different emotions is reflected clearly? For it is precisely with vocal music that different emotions can be achieved through the sound of the vowels – they can be much more differentiated than the surrounding consonants.

And last but not least, of course, the casting of the solo parts, alongside the important components of choral and orchestral quality is the crux of the dramatic interpretation. We do not need to say any more about the versatility required for the title role. But how many sopranos are there who can begin the aria “Hear ye, Israel” with a soft F sharp which nevertheless soars above the orchestra. Mendelssohn raved about the singing of soprano Jenny Lind, whom he so greatly admired.

Of course it is not easy for characterful vocal performers to also blend skilfully into a soloistic ensemble sound, as Mendelssohn requires from his soloists in the chorale “Cast thy burden upon the Lord”. This is why I have the chorus sing this chorale in performances – it results in a comparable sound to the chorus “He that shall endure to the end” with its sense of assurance. But by the end of the work the soloists need to have found a way to create a unified quartet, with their combined “O come every one that thirsteth”. After singing their solo parts this can be easier at the end of the work, easier than in the first third where they have to sing together in a double quartet “For He shall give His angels charge over thee” with four other soloists, creating a blended sound.

Perhaps a more homogeneous sound in this double quartet can be achieved by using soloists from the chorus?

There is only space to briefly mention some other particularly striking word and music connections important for performances: the sighing oboe of the widow in the dialogue scene with Elijah; the Prophets’ entry motif, constantly shifting through different keys; the ascending major triad for the light out of the darkness, and the ascending scale of the Prophet to heaven, accompanied by accentuated syncopations and quasi tremolando sixteenth note triplets.

Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy. Oratorios

- CD-Box (4 CDs): Carus 83.021/00

Kammerchor Stuttgart

Die Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen

Klassische Philharmonie Stuttgart

Conductor: Frieder Bernius

Elijah is Mendelssohn’s last vocal work, crowning his entire output. To do it full justice, it is helpful to have a thorough familiarity with his extensive vocal works, with which the composer prepared the building blocks for this magnificent piece.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!