“Yea, though I walk through death’s dark vale …”

Psalm settings as a cry for help and comfort

At a time of great changes in which the uncertain, the unpredictable, indeed, even the unsettling can become the new normal, it is the psalms in particular which can offer comfort, confidence, and hope – not only for believers, but also for people who have little or no faith.

The psalms are a cohesive group of poetic songs in the Old Testament and are amongst the oldest texts written from the perspective of the individual. It is the only book in the Bible in which man talks exclusively to God, not God to man. The texts were written at a turbulent time more than two-and-a-half thousand years ago and express the whole range of human emotions, from the darkest despair, anger, and the all-too human thirst for revenge, to thankfulness, joy, and deep religious faith.

The humanity of the psalms and their lyrical qualities have inspired composers for over a thousand years. The fact alone that these texts are still a living tradition today and that they have influenced generation after generation is reflected in their exceptional strength and depth. In their diversity, settings of the psalms offer a rich resource from which varied concert programs can be compiled.

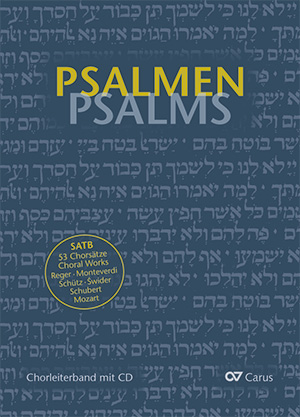

CHORAL COLLECTIPON PSALMS

ed. by Stefan Schuck

- Over 50 psalm settings from six centuries for worship and concert use

- Stylistic variety and mixed levels of difficulty: from Anglican Chant to virtuoso motets

- For four-part mixed choir, occasionally with organ/piano accompaniment

As a suggestion, we present a program here which is conceived for an unaccompanied concert by a mixed choir, not tied to any particular season of the church year. The duration is c. 45 minutes.

Josef Gabriel Rheinberger (1839–1901): Warum toben die Heiden

Josef Gabriel Rheinberger’s dramatic four-part motet contrasts all-too human pride, vanity, and anger with the peace which is created from trust in God. In Babylonian exile, the singer of the psalms presents an all-too-human God who is capable of punishing and destroying.

Loys Bourgeois (1510–1559): Las en ta fureur

Claudio Monteverdi (1567–1643): Domine in furore tuo

Two very different pieces from the Renaissance give an extremely impressive expression of the fear of God’s judgement: In Loys Bourgeois’s setting of Psalm 38 in the French translation by Marot from the Genevan Psalter, an almost resigned plea is heard despite the strict polyphonic style of the piece. This was probably driven by the Huguenot composer’s own experiences of persecution and hostility. The Catholic composer Claudio Monteverdi set a similar text from Psalm 6 (Domine, ne in furore tuo; O Lord, rebuke me not in thine anger). This motet in six parts (the bass and soprano parts divide) is in a somewhat more extrovert style, crying out to God as a “vexed soul”, “But thou, O Lord, how long?”

Heinrich Schütz (1585–1672): Ich harrete des Herren

The text of Psalm 40 ushers in a change of perspective, here in a homophonic four-part setting from the Becker Psalter by Heinrich Schütz, which follows on well in terms of key. In this hymn-like psalm setting, God is portrayed as the gracious, the sublime, who did not desire any sacrifice. But here, too, human emotions come to the fore when the singer in the 9th verse demands that God allow those who “mir nach der Seelen stehen” “mit Schmach zu Boden gehen” (“seek after my soul … be driven backward and put to shame”). By alternating the voices used, or by perhaps just having the sopranos sing the melody, the sequence of verses can be made interesting and varied.

Franz Josef Schütky (1817–1893): Emitte spiritum

This short work by Schütz leads into three Romantic settings. The eight-part gradual by the Stuttgart singer and conductor Franz Josef Schütky is a real discovery with its double-choir Romantic sonority. It combines a line of text from Psalm 104: “Emitte Spiritum tuum, et creabuntur; et renovabis faciem terrae” (“Thou sendest forth thy spirit” and “thou renewest the face of the earth”) with two lines from the Whitsun hymn “Veni Sancte Spiritum”. This and the following texts praise God as protector, renewer, and support, as a God who gives people confidence and strength.

Georg Schumann (1866–1952): Und ob ich schon wanderte im finstren Tal

Georg Schumann, a former conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic Choir, little known today, composed three sacred unaccompanied motets at the beginning of the 20th century, which are also an interesting rediscovery. In four parts almost throughout, there are a couple of small divisions in all the vocal parts. The “valley of the shadow of death” through which we walk on the earth is expressed in rich harmonies, and is effectively contrasted with the comfort of God’s guiding shepherd’s crook; a great, harmonically interesting, calming unfolding of sound.

Jessie Seymour Irvine (1836–1877): The Lord’s my shepherd

A hymn setting by the Scottish composer Jessie Seymour Irvine with the text of Psalm 23 became very well-known. A soprano descant to this simple setting is very effective, and can easily be sung by a good amateur soloist, so that the five verses can be presented in a musically varied way.

Tomás Luis da Victoria (um 1548–1611): Benedicam

Joseph Haydn (1732–1809): Non nobis domine

Anonymus (17. Jahrhundert): Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele

The following three psalm motets praise God’s goodness in a contemplative, inspired way. The Spanish Renaissance master Tomás Luis da Victoria expresses praise in a perfect cantabile polyphony with words from Psalm 34; a four-part composition which can readily be tackled by choirs with little experience of Franco-Flemish vocal polyphony, is undaunting, and very effective.

Over 200 years later Joseph Haydn set the beginning of Psalm 115 “Non nobis Domine” (“Not unto us, O Lord”) in the stilo antico in a contrapuntal setting, thereby seamlessly continuing the style of Victoria. The continuo part which Haydn provided here can be omitted almost without any loss to the overall texture, but offers good support.

A short four-part setting by an anonymous 17th century composer of Psalm 103 – “Lobe den Herrn, meine Seele” (“Bless the Lord, O my soul”) continues the inspired hymn of praise in spirited fashion. This fine work should be taken at a brisk tempo throughout, and any temptation to slow down by the long note values should be resisted.

Ko Matsushita (*1962): Bonum est confiteri

A very worthwhile challenge for chamber choirs with sufficient forces is the Japanese composer Ko Matsushita’s motet setting of Psalm 92, which praises God’s works lyrically and cheerfully. As early as pre-Christian times it belonged to the liturgy of Sabbath worship. Matsushita has set the psalm in motet style, much inspired by the Catholic liturgical Gregorian melody of the antiphon of the same name and a well-known Halleluja on the 8th tone. His hymn of praise begins almost modestly and humbly, and significantly it omits the martial-sounding verses of the psalm. Only in the concluding “Halleluja” does the composition intensify through a dance-like rhythmic figure to fortissimo, to then return to the introverted opening mood. This piece can form a brilliant conclusion to a program, even though it fades away in pianissimo.

Max Reger (1873–1916): Ich liege und schlafe

“Ich liege und schlafe ganz in Frieden” (“I lie down and slumber, deeply at peace”), the chorale from Max Reger’s motet “Ach Herr, strafe mich nicht” depicts the mood of peace wonderfully. It expresses trust in God and deliverance and thus releases the listener into everyday life strengthened and with confidence.

Translation: Elizabeth Robinson

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!