CREDO … I believe

1700 years of the Nicene creed

In most mass compositions, the text that will be celebrated in 2025 is central: The Nicene Creed. At the Council of Nicaea in 325, 1700 years ago, the process of agreeing on a creed was initiated. The final form of the Nicene Creed is the only creed to which all Christian churches around the world refer. Prof. Dr. Stefan Klöckner on the history of its creation and the Creed as an artistic inspiration.

Credo. Six Composers – Six Parts – One Christian Faith

Commissioned Composition for the 1700 Anniversary of the Nicaean Credo

Carus 7.461/00

In common usage, the meaning of the word “believe” is simply “I don’t have proof for what I think” (or even “I can’t have proof”). “Believing” something or someone, therefore, is subordinate to our fact-based knowledge. If you truly “know” something, you don’t have to “believe” it anymore.

However, the history of Christian belief in God – which rests on the shoulders of Judaism and is inconceivable without its intellectual heritage – speaks a different language: Belief or faith is “the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.” That’s how the author of the New Testament letter to the Hebrews (Heb. 11:1) put it around the year 60 AD. Firm conviction – the certainty of belief – thus becomes the supporting foundation of a life lived under God.

Early creeds

Even in the Old Testament, we find various statements that encapsulate the meaning and importance of faith. For example, we find acknowledgements of the one true and only God (“Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God is one LORD”, Deut. 6:4) as well as reminders of God’s divine interventions and his interactions with us humans (“My father was a wandering Aramean …”, Deut. 26:5).

The early Christians also began to express their faith in statements of confession: a first creed – still written in Greek and then translated into Latin – was formulated around the year 130 AD. It already contains all the essential thoughts of the later Nicene creed: God is the Father and Creator; his only begotten Son, Jesus Christ, came into the world as a human being; he died and rose again to redeem us; the Holy Spirit and the Church are continuing God’s and Jesus’ work of salvation until the Day of Judgement, when all the dead will rise to enjoy eternal life.

In the following centuries, this core text was continually revised and expanded, in particular to counter the various heresies that sprouted up in the early Christian church. To this end, precise statements were formulated about Jesus Christ as a “true God” (Deum verum de Deo vero) and at the same time a “true man”, who lived in a specific historical period (born at the time of King Herod, died during the governorship of Pontius Pilate – sub Pontio Pilato). The statements from the 4th century that Christ was “begotten, not made” (genitum, non factum) and was “consubstantial with the Father” (consubstantialem Patri) were intended to refute the theological teachings of a man called Arius, who rejected the notion of Jesus Christ as an equal part of the divine Trinity. Arius saw the danger that the co-divinity of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit could be misunderstood as a belief in three Gods.

First Council of Nicaea

Icon of Michael Damaskenos (1591)

The Great Creed: origins and development

1700 years ago, in 325, an assembly of Christian bishops met in Nicaea (near present-day Istanbul) on the orders of the Roman Emperor Constantine. This was the first major council convened to resolve religious disputes. At this and the subsequent assembly in Constantinople in 381, the bishops rejected the teachings of Arius, formulating the so-called “Niceno-Constantinopolitan” creed. This became official Christian doctrine after it was first proclaimed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451. And it is still valid today!

However, two words in this important and lengthy text served to divide theological opinion. The “East-West Schism” (or “Great Schism”) of 1054 saw the Orthodox Church split from its Roman sisters and brothers due to the inclusion (amongst other things) of the word filioque, which implied – to the consternation of Eastern theologians – that the Holy Spirit emanates not only from God the Father, but also from his Son, Jesus Christ.

And, to this day, the word “catholic” (et unam sanctam catholicam et apostolicam ecclesiam – I believe in the one holy catholic and apostolic church) is a thorn in the side of Protestant churches, as it is difficult to avoid the misunderstanding that here catholicam refers solely to the Roman Catholic Church. This is clearly not the case if we turn to the original meaning of the Greek word kat’holon, which is comprehensive or general. For this reason, the German-language Protestant version of the Nicene creed contains a slightly different formulation, according to which we believe in the “one, holy, all-encompassing (or: Christian) and apostolic church”.

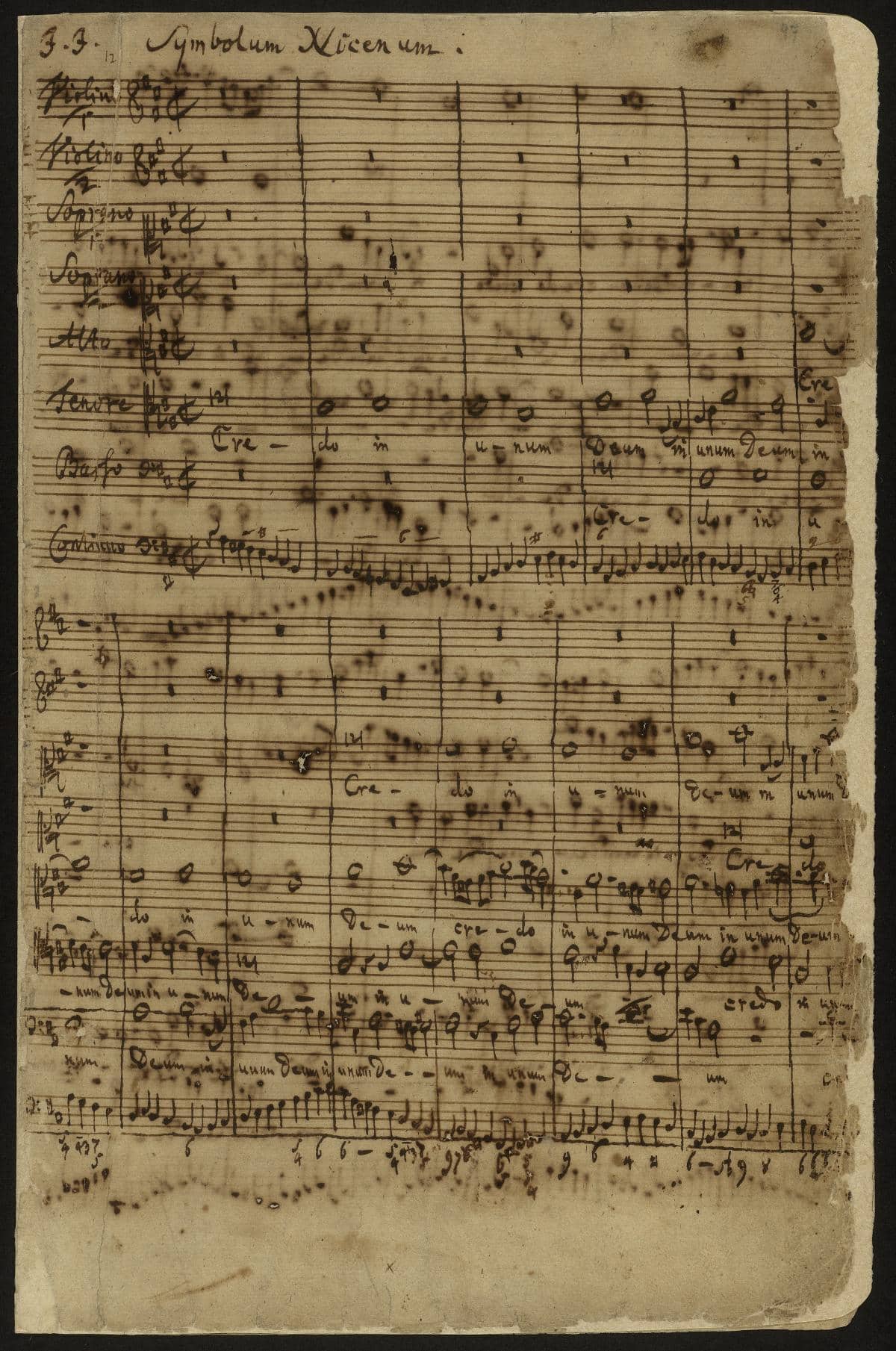

Anyone looking at the title page of the “Credo” setting in Johann Sebastian Bach’s B minor Mass will notice the title “Symbolum Nicenum”. In the early Christian church, a statement of faith was referred to as a “symbolum”, referring back to the ancient notion of a symbol as a sign that marks an “insider” from an “outsider”– a ticket, so to speak, that permits entry. In the religious understanding, this means that baptized persons who wish to take part in the Eucharist (the Lord’s Supper) must first profess their Christian faith, making clear that they are “kyriaké”, a Greek word which can be translated as “belonging to the Lord (Christ)”. This term is in fact the origin of the German word for church: “Kirche”.

That’s why reciting or singing the creed during the Sunday service is so fundamental. Whether Catholic and Protestant, it is intoned after the reading of the Holy Scriptures and the sermon, whose aim is to interpret the Scriptures and translate these into contemporary language relevant to modern-day Christians. After the sermon, the members of the congregation respond by affirming their faith.

The creed as artistic inspiration

Since the 14th century, the Credo has been part of the Ordinarium Missae, which is the set of Mass texts whose form and placement in the service never varies: Kyrie – Gloria – Credo – Sanctus (with Benedictus) – Agnus Dei. The Credo settings of the Classical and Romantic periods (e.g. by Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Schubert, Gounod, Bruckner and Puccini) are particularly expansive and musically varied due to the length of the creed text. Here the main events of Jesus’ life are usually treated in different ways: The conception by the Holy Spirit (Et incarnatus est) is often entrusted to soloists and set in a slow, intimate and restrained tonal language, while Christ’s suffering and death (Crucifixus etiam pro nobis) and the resurrection (Et resurrexit tertia die) are realized in a dramatic manner using all available musical means. We also see this in recent musical settings: modern composers still view the Credo as a text that invites artistic exploration. And this also applies to a number of individual settings of the Credo, for example by Antonio Vivaldi or Krzysztof Penderecki.

If today – 1700 years after the creation of the Nicene creed – we intensively study and listen to its settings, then this is perhaps less as an aural manifestation of the Christian faith or an attempt to distinguish “true” religious tenets from false or different beliefs. Instead, the focus today is more on the musical exploration of various urgent questions facing humanity that transcend all religions and denominations, and which have been rendered into sound by composers throughout the ages: Why am I here? What is guilt and what is redemption? What will happen after my death? What does “hope” sound like? The Christian answer to these questions is, on the one hand, a comfort to the human soul, and, on the other, a challenge to the reflective mind…

Prof. Dr. Stefan Klöckner, born in Duisburg in 1958, is Professor for Musicology at the Folkwang University of Arts and a leading expert on Gregorian chant and the history of church music. Among other things, he was head of the Office for Church Music of the Diocese of Rottenburg/Stuttgart, founded the internationally renowned ensemble VOX WERDENSIS and teaches in Germany and Switzerland on music, theology and their connections.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!