Camille Saint-Saëns

a very personal portrait

Camille Saint-Saëns was one of the outstanding personalities in French musical life – as composer, teacher, and organist. For 20 years he worked at the Église de la Madeleine, one of the most important churches in Paris with its Cavaillé-Coll organ. But many of his works have now fallen into oblivion. Yet, in the opinion of Denis Rouger and others, this exceptional musician cannot be highly enough appreciated. Both Rouger’s own work at the Madeleine Church and his family history connect him to the composer.

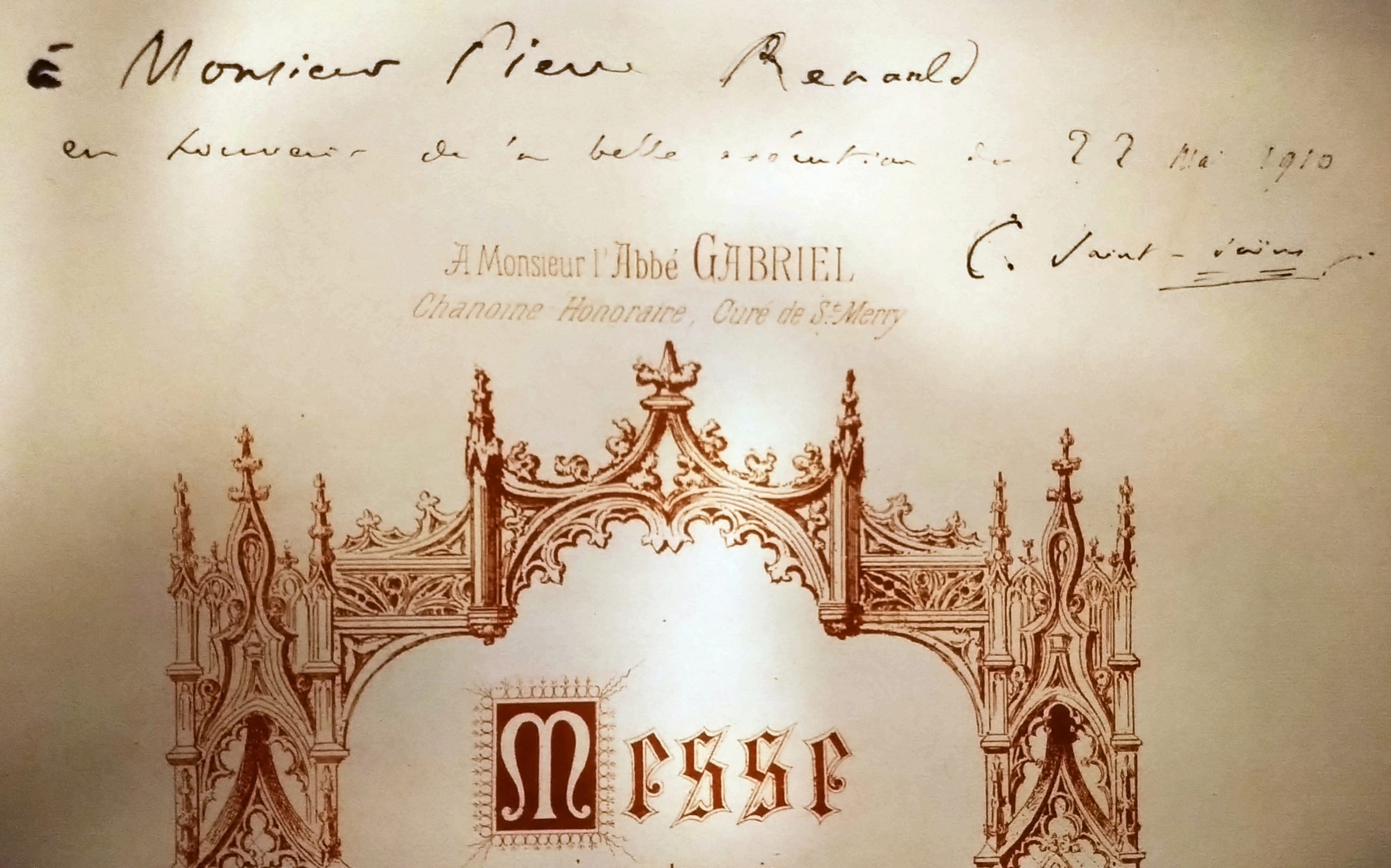

My grandfather Pierre Renauld, who went on to become deputy music director at the Opéra Comique in Paris, was a choral director at the beginning of the 20th century. It is an almost outrageous thought that he experienced the first performance of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, and that he spoke personally with Debussy and Fauré! In 1910 he performed Saint-Saëns’ Mass op. 4. When my mother was sorting out her music library one day, she found a copy of this Mass. Opening the first page, she found a personal dedication to my grandfather from Saint-Saëns. “Pour Monsieur Pierre Renauld en souvenir de la belle exécution du 22 mai 1910”. For Monsieur Pierre Renauld as a souvenir of the beautiful performance on 22 May 1910 Camille Saint-Saëns. We know that the two musicians were also close friends later on; for example, Saint-Saëns sent my grandfather various postcards during the summer, all of which are wonderful documents of music history for me, and at the same time personal heirlooms which I treasure.

Saint-Saëns: Ave verum in Es

CD Carus 2.311/97

Score Carus 2.311

Ultimately Camille Saint-Saëns (1835-1921) became one of the most important figures on the French music scene. He was a child prodigy and began playing the piano at the age of three. At the age of eight he began studying harmony and piano, and he was barely eleven when he gave his first concert. He also studied organ and composition, and at the age of 18 he took up the position of organist at the church of Saint-Merry and later, in 1857, at the Madeleine, where he remained for twenty years and became known for his spectacular improvisations and much else besides. Saint-Saëns gave concerts throughout the world on the piano and organ, as well as composing and teaching. Berlioz, Wagner, and Liszt were amongst his friends and admirers, and Clara Schumann visited him. Liszt dubbed Saint-Saëns “the greatest organist in the world” and later helped him to have his opera Samson et Dalila performed. In return, Saint-Saëns dedicated his marvellous 3rd Symphony with organ to Liszt. It is said that one day, Saint-Saëns played the entire opera Tristan from memory on the piano to an astounded Wagner, and sang all the parts as well (in his terrible piercing voice).

As a composer Saint-Saëns wrote a tremendous amount: besides 13 operas he composed many concertos, symphonies, chamber music, program music, songs, even music for a film, and sacred music. Yet although he was world-famous as a composer, his works were often criticised. Perhaps because he was not regarded as a revolutionary or at least an innovator, although he was alive when Fauré, Debussy, Stravinsky, Bartók, and Schoenberg were writing their masterpieces. Saint-Saëns composed most of his works before 1896; at the beginning of his career his music was felt to be too modern, and at the end, too traditional.

But we should on no account forget that Saint-Saëns provided much inspiration, and supported and influenced many students and composers. As a professor he based his teaching on German music and taught Gabriel Fauré, Paul Dukas, and many others very open-mindedly, and with role models such as Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and Mendelssohn. Because he feared the French musical tradition could disappear he founded the “Société nationale de musique”, which brought him accusations of nationalism. Perhaps history has honored him too little as a person, because he hated self-promotion. He was an extremely sensitive, delicate, kind, and humorous man, incredibly broadly educated and incredibly generous: he gave lots of money to anyone who was in need. In the end he died in great poverty.

Tollite hostias, from:

Saint-Saëns: Oratorio de Noël

CD Carus 83.352

Score Carus 40.455

carus music, the choir app Carus 73.302

Strangely enough, much of Saint-Saëns’ work has not been published and many works remain unknown. At first glance, his church music may seem to be well-composed, but that is precisely what was expected of him at the Madeleine. There is the story of his successor Gabriel Fauré, who went back into the sacristy after the first performance of his beautiful Requiem (Carus 27.312), where he was reprimanded by the priest (“We don’t need music like that!”). For Saint-Saëns it was the form which had priority, and inspiration and structure were to constantly run in parallel. The short Ave Maria in F major (included in the Carus collection French Choral Music Carus 2.311) is a good example of this: the music seems to be unbelievably simple, almost plain. But when it is performed with calm in a special acoustic such as in the Madeleine, an impression of the purest emotion is created which sensitively describes the prayer to Mary. We should also always bear in mind the catastrophic situation of church music in France in the 19th century: the quality of the music was alarming in many places, for example, operatic arias were often heard in church services quickly provided with sacred texts without any care. What appears to us at first glance as simple and plain is often thanks to the composer’s striving for purity, and we can be grateful to Saint-Saëns that he showed a way which was able to inspire other composers. His sacred output comprises 30 Latin motets (many for one or two voices), a Requiem (Carus 27.317), the early Mass (Carus 27.060), the Oratorio de Noël (Carus 40.455) and four French Cantiques.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!