Ravel and the Rome Prize

– a tale of failure

Maurice Ravel took part in the prestigious Prix de Rome competition, but despite his tireless efforts, he never managed to win the first prize. The year 1905 in particular led to a scandal: Ravel was disqualified in the preliminary round, which triggered public protests. However, his works from this period, including fugues, choral compositions and cantatas, show his extraordinary talent and his ability to combine strict academic guidelines with creative orchestration and harmony.

Between 1900 and 1905, Maurice Ravel took part five times in the competition for the Rome Prize, the Prix de Rome, but never succeeded in winning the first prize. His perseverance, however, indicates the importance he attached to this competition. Taking part was no easy matter: one had to prepare for difficult tests and accept a strict set of rules. The competition consisted of two rounds. The first round, the Concours d’essai, consisted of a six-day exam in a cubicle, a so-called “loge.” During this time, the participants were not allowed to leave the competition venue (the Palais de Compiègne in Ravel’s day) or communicate with anyone. The task was to write a fugue for four mixed voices and a composition for choir and orchestra. Those who successfully passed the Concours d’essai were then allowed to take part in the thirty-day main competition, the Concours définitif. The work to be composed here remained a characteristic feature of the Prix de Rome: it was a lyrical scene for two or three solo voices and orchestra, generally designated a “cantata.” From 1845 onwards, the text to be set to music was itself the subject of an annual poetry competition on mythological, historical, legendary, novelistic or even biblical themes.

The “Ravel affair“

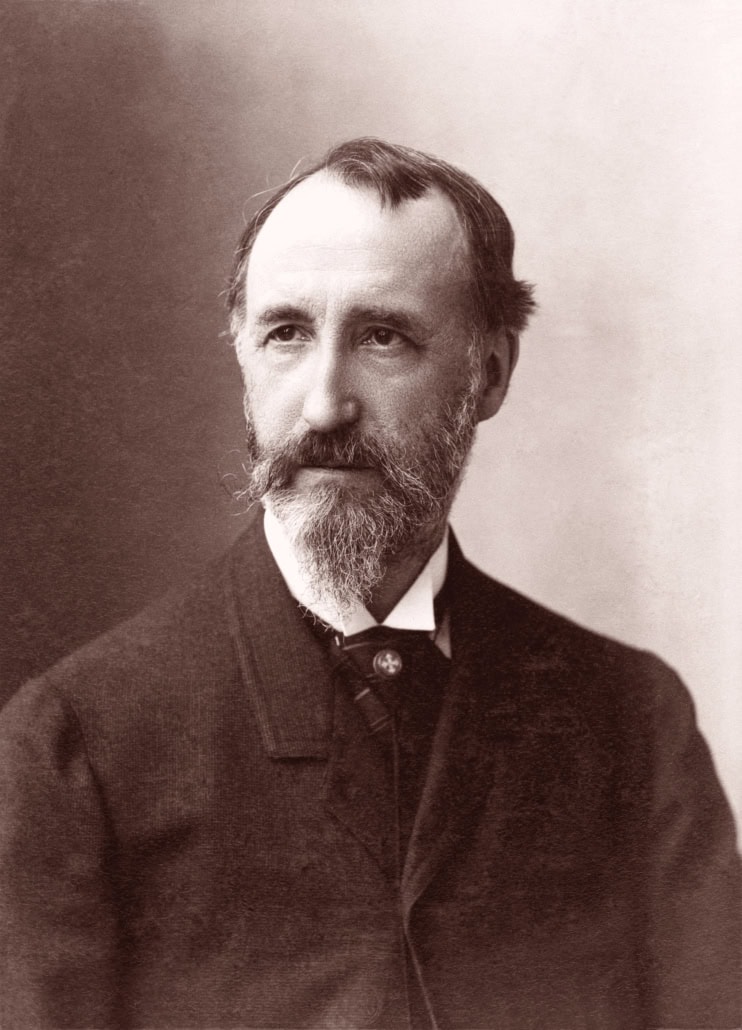

After not competing in 1904, Ravel attempted to win the Rome Prize for the last time in 1905. But he was eliminated in the preliminary round, which led to fierce protests that were echoed by the contemporary press. One reason why this decision was contested was that four years earlier, the jury had awarded Ravel a “second second prize,” and it was therefore difficult to understand why a prizewinner from 1901 should no longer be admitted to the competition in 1905. In view of the fact that Théodore Dubois, the director of the Conservatoire, held a negative attitude towards Ravel, it is not impossible that he was able to influence the jury’s decision. Dubois, who represented a traditionalist attitude in the musical France of the time, openly opposed modern musical developments, of which he considered Ravel to be a representative. Another problematic aspect was that all the candidates selected at the Concours d’essai were pupils of Charles Lenepveu: Louis Dumas, Marcel Rousseau, Philippe Gaubert, Louis-Ferdinand Motte (known as Motte Lacroix), Victor Gallois and Abel Estyle. As a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, Lenepveu was also a legitimate member of the jury by virtue of his position.

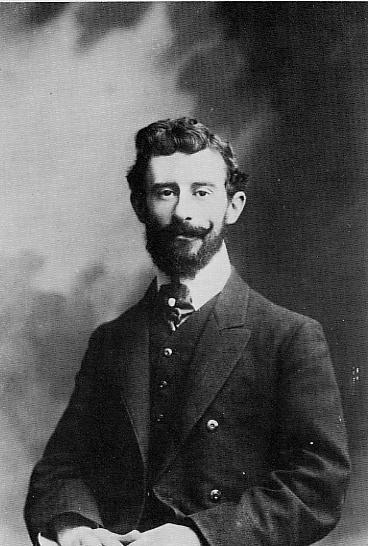

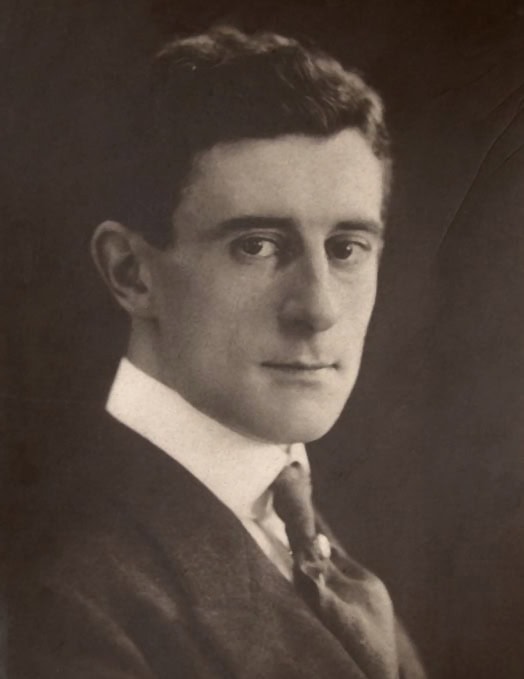

Maurice Ravel, 1906

Théodore Dubois

The result of the Concours d’essai could therefore be regarded as a sign of a lack of neutrality. Shortly after the Prix de Rome scandal, Théodore Dubois resigned from his post as director of the Conservatoire. However, it was demonstrated that this resignation, which had previously often been seen as an admission of guilt, was not connected to the “Affaire Ravel”: a number of documents show that Dubois had already requested his retirement several months earlier in order to devote himself to his musical activities and to recover from a position that had exhausted him.

Ravel’s compositions for the competition

The pieces that Ravel composed for the Prix de Rome competition are neither quantitatively nor qualitatively insignificant. They include the pieces composed for the Concours d’essai, i.e., five fugues and as many choral works, as well as the cantatas of 1901, 1902, and 1903, since Ravel had passed the preliminary round in those three years.

The Fugues

The fugues correspond to a type of task that was required throughout the history of the Prix de Rome and was referred to as the “school fugue” at the Paris Conservatoire. The rules for this genre were laid down in treatises on counterpoint and fugue from various eras, e.g., by François-Joseph Fétis (1824), Luigi Cherubini (1835), Théodore Dubois (1901), André Gédalge (1901), and Marcel Dupré (1936). The students had to adhere to a strict formal structure and demonstrate their mastery of demanding contrapuntal techniques (augmentation, diminution, inversion, retrograde, canon etc.). The manuscripts of the fugues written for the Rome Prize show traces of this academic practice, as the candidates themselves noted down indications which could be used to track the obligatory procedure as well as the contrapuntal modifications. Even though the winners of the Rome Prize did not always have occasions to write fugues in the course of their composing careers, mastery of counterpoint in general and of the fugue in particular was considered essential for a composer. For example, Georges Bizet, winner of the Rome Prize in 1857, applied his contrapuntal skills to the composition of a Te Deum (Carus 27.187) during his stay in Rome in 1858. He conceived its fourth movement (“Fiat misericordia tua”) as a large fugue for choir and orchestra. Ravel, however, seems to have shown little interest in studying the fugue. In his day, the possibilities for applying this compositional technique were already very limited, especially for a composer who represented an avant-garde approach. Nevertheless, his three-part fugue in Le Tombeau de Couperin (1914–1917) deserves mention, and should be regarded in the light of a homage to an 18th-century composer.

The choral compositions with orchestra

The choral work with orchestra and soloist, which was also required in the Concours d’essai, was composed to a poem by an author held in high esteem by the members of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. In the case of Ravel’s composition L’Aurore (Carus 10.407), submitted in 1905, the poet was Édouard Guinand, an author who had already provided the text for the cantata L’Enfant prodigue in 1884, with which Claude Debussy won first prize. L’Aurore describes an idyllic view of nature at sunrise and celebrates the sun almost as a deity for its beneficial influence on nature and mankind. The choral composition was used to assess the candidates’ skills in terms of orchestration, but also in dealing with a poetic text, both from the point of view of the correspondence between music and text and from the more technical aspect of prosody. Even if the exact scoring was not specified, the choral compositions of the competition in Ravel’s time included at least one solo voice in addition to choir and orchestra. In L’Aurore, the soloist is a tenor who appears at the center of the piece with a salutation to the rising sun.

L’Aurore inaugurates the edition of all five choral competition compositions published by Carus (10.403–10.407). Of the five, this composition is probably the most typical of Ravel. One finds idiosyncrasies in the orchestration and harmony that Ravel had already implemented in works composed around the beginning of 1900: In terms of harmony, one notices, for example, the frequent use of the triad with sixte ajoutée, of parallel fifths and pedal points, the use of “modal” colorations (Dorian, Phrygian) and selective dissonances, without taking into account the usual rules of preparation and resolution. In terms of orchestration, Ravel liked to use tremolos (possibly combined with pizzicati), solo winds, harp glissandi, accompaniment by triplet or sixteenth-note figurations and recitative-like instrumental sections.

The other choral compositions written between 1900 and 1904 are likewise of far greater musical interest than mere practice or study pieces. In Les Bayadères (1900, Carus 10.403, in prep.), the orientalizing atmosphere of the poem by Henri Cazalis gave Ravel the opportunity to try out an “exoticism” which he refined in Shéhérazade (1903) and which also reveals strong similarities with the Hispanicizing style that became a recurring element in his work from the Rhapsodie espagnole of 1907 onwards (e.g., the use of the tambourine and the rhythm ![]() ). In Tout est lumière (1901, Carus 10.404, in prep.), he was inspired by the romantic poetry of Victor Hugo to write a piece in a more conventional style, but with an equally masterful use of orchestral timbres. La Nuit (1902, Carus 10.405, in prep.) offered Ravel the opportunity to demonstrate a wide variety of different writing styles in one short piece: We find, for example, a cappella choral phrases, but also a soprano section accompanied only by a reduced orchestra (chordal repetitions in the winds as well as arpeggios in the harp). This principle of a solo part accompanied in a restrained manner by the orchestra is taken up again in Matinée de Provence (1903, Carus 10.406, in prep.). As in L’Aurore, an idyllic morning landscape is also depicted here. But even if the sun is also very present in Matinée de Provence, the poet, whose identity will only be revealed in the Carus edition to be published in 2025, is primarily concerned with emphasizing the beauty of his region, the Provence.

). In Tout est lumière (1901, Carus 10.404, in prep.), he was inspired by the romantic poetry of Victor Hugo to write a piece in a more conventional style, but with an equally masterful use of orchestral timbres. La Nuit (1902, Carus 10.405, in prep.) offered Ravel the opportunity to demonstrate a wide variety of different writing styles in one short piece: We find, for example, a cappella choral phrases, but also a soprano section accompanied only by a reduced orchestra (chordal repetitions in the winds as well as arpeggios in the harp). This principle of a solo part accompanied in a restrained manner by the orchestra is taken up again in Matinée de Provence (1903, Carus 10.406, in prep.). As in L’Aurore, an idyllic morning landscape is also depicted here. But even if the sun is also very present in Matinée de Provence, the poet, whose identity will only be revealed in the Carus edition to be published in 2025, is primarily concerned with emphasizing the beauty of his region, the Provence.

Maurice Ravel, ca. 1910

The cantatas

The cantatas were more demanding pieces than the choral compositions of the preliminary competition. By means of this compositional task, the candidates were to further develop their basic skills in the field of opera, which was the main objective of the Conservatory’s composition classes. This previously neglected repertoire is now better known and is performed in concerts and recordings, especially the cantatas of composers who have become famous such as Berlioz, Debussy, and Ravel.

The cantata genre was subject to numerous specifications, beginning with a prescribed text whose theme could differ significantly from the literary preferences of the candidates. In Ravel’s time, the cantata was scored for three persons, i.e., three soloists were required. Formal conventions included opening the cantata with an orchestral introduction, and the successive appearance of the characters, which often resulted in a love duet when the second person appeared. The arrival of the third person created a twist in the existing situation and had to lead to a trio communicating in dialog which included a contrapuntal section.

The three cantatas composed by Ravel reinforce the significance of these conventions: In Myrrha (1901), the characters of King Sardanapalos and the slave girl Myrrha, with whom he has fallen in love, sing the love duet. The third figure, the high priest Belesis, prevents Sardanapalos from fleeing with Myrrha and thus escaping the funeral pyre. Alcyone (1902) is structured differently; there is no love duet. Instead, the second character, Sophrona, Queen Alcyone’s confidante, is present from the very beginning. Céyx, Alcyone’s deceased husband, appears to her as a shadow in the fourth scene. In Alyssa (1903), which is set in Ireland in the time of the sagas, the conventional structure is found again: the love duet is sung by Prince Braïzyl and the fairy Alyssa. The third character is a bard who wants to tear Braïzyl from Alyssa’s arms and persuade him to defend his people, who are under attack from the warriors of Morven.

A closer look at the cantatas shows that Ravel placed very high demands on the vocal solos: his sung roles require strength and are often demanding in the high register. These vocal demands also applied to opera, the noble genre for which the cantata served as a field of experimentation – albeit on a small scale, but nevertheless significant enough to require solid compositional skills (Ravel’s three cantatas are each around 25 minutes long). As in the choral compositions, the orchestra is also very present in the cantatas. Ravel deploys many individual combinations of timbres, but he also demonstrates his knowledge of the symphonic style of French composers such as Franck or Saint-Saëns. The traditional opportunity to show off his orchestral skills would be in the introduction, but in Alcyone, Ravel inserts a “Symphonic Description” lasting around four minutes after the first scene, in which he primarily depicts the storm in which Céyx perished. In the cantatas, Ravel uses the orchestra as a timbre, but also entrusts it with the introduction and development of leitmotifs in a way that the French had copied from Wagner and which characterized Massenet’s technique, for example.

The extensive group of pieces composed by Ravel for the Prix de Rome thus proves to be extremely substantial. One can sense in it the uncomfortable position of a composer whose personal style, already consolidated and appreciated by the public, shines through again and again, but who, on the other hand, endeavors to satisfy the jury by mostly choosing a more consensual way of writing, based on the appropriation of the styles of composers such as Massenet, Saint-Saëns, Chabrier, Bizet and others. The five compositions for chorus, soloists and orchestra presented above, which are successively being published by Carus, offer an excellent impression of Ravel’s inventiveness, which enabled him to overcome academic constraints and succeed in demonstrating a particular creativity with respect to orchestration and harmony, capturing the essence of a poetic text in a highly sophisticated musical rendering.

Marc Rigaudière is a professor of musicology at the University of Reims and at the Center for Research and Higher Education in Cultural History (CERHiC) there. He previously taught at the conservatory in Metz and at the Sorbonne University in Paris, among other places. His main fields of research are music theory and musical analysis, as well as the scholarly edition of musical works, in which he has been collaborating with Carus-Verlag since 2002.

Over three verses, Aurore describes the approaching dawn through an intensifying piano accompaniment: shining out like fading stars, the short quarter notes in the first verse in G major give way in the second verse to a rippling sixteenth note accompaniment in the minor key. This art song was originally composed not for chamber choir, but for solo voice and piano. Denis Rouger has carefully adapted it to suit the requirements and expressive possibilities offered by a larger ensemble, without losing any of the qualities of the original in the process.

Over three verses, Aurore describes the approaching dawn through an intensifying piano accompaniment: shining out like fading stars, the short quarter notes in the first verse in G major give way in the second verse to a rippling sixteenth note accompaniment in the minor key. This art song was originally composed not for chamber choir, but for solo voice and piano. Denis Rouger has carefully adapted it to suit the requirements and expressive possibilities offered by a larger ensemble, without losing any of the qualities of the original in the process. In the winter of 1914/1915, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, Maurice Ravel composed his Trois Chansons as settings of his own texts. With these three musical stories Ravel managed to create little jewels of a cappella choral literature, even In the midst of the “nightmare”, as he himself described the times.

In the winter of 1914/1915, shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, Maurice Ravel composed his Trois Chansons as settings of his own texts. With these three musical stories Ravel managed to create little jewels of a cappella choral literature, even In the midst of the “nightmare”, as he himself described the times.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!