A socialite with a great sense of humour?

Gaining insight into the personality of Johann Sebastian Bach

What do we actually know about the personality of Bach over beyond the idealization of the Cantor of St. Thomas and even deification? It is only possible to compile cautious assumptions about his personal manner with the aid of sparse surviving comments by himself or his contemporaries. Some of his secular cantatas depicting the social life of his time hint at humorous and light-hearted character traits.

One of the most difficult tasks in musicological research is gaining an accurate image of Johann Sebastian Bach’s personality. It would be presumptuous to attempt a comprehensive approach, as surviving sources barely permit an extensive interpretation of this aspect of the composer. This state of affairs is most likely also intended by Bach himself and was perhaps best expressed by Hindemith who spoke of the “oyster-like taciturnity” of the composer. Bach’s ostensible reticence is not only observed in his private correspondence, but also in the rare allusions to Bach’s personality in descriptions provided by his contemporaries and recollections by his sons and pupils. We do not know why Carl Philipp Emanuel and Johann Friedrich Agricola virtually skirted round a comment on his character in their obituary compiled at the end of 1750, preferring the vague general statement that “those who enjoyed his company and his friendship and were witnesses of his integrity towards God, and his nearest and dearest are in the best position to talk about his moral character.”

“peaceable, calm and serene”

Mentions of his family and private sphere are rare in Bach’s few personal letters and then only within a marginal context. It was perhaps a lack of elegance with the quill possibly coupled with the absence of a need to communicate which could have prevented him from describing his personal circumstances in great detail. Even if we have to assume that a large proportion of Bach’s correspondence has been lost, it is still somewhat strange that external events and his permanently full engagement diary – particularly after 1723 – did not prompt him to become an active letter-writer. Admittedly, his heavy workload genuinely left him with little space for personal matters. Unfortunately, the surviving sources mostly reveal circumstances regarding deviations from normal working regulations and other legalities which provoked spontaneous disputes and often extended conflict. Other frequent themes include arguments on matters of competence and financial affairs. The state of normality in the everyday life of the Cantor of St. Thomas which was mostly “peaceable, calm and serene” in which he only “became antagonized and sought to express his fervor in the strongest expressions” on exceptional occasions remains completely unmentioned. Admittedly, we cannot judge today whether these remarks made by Carl Ludwig Hilgenfeldt in 1850 really corresponded to actual fact, although the Bach biographer at least had recourse to information indirectly going back to Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.

Any information on Bach’s everyday life, his preferences, dislikes, strengths and weaknesses can only be incidentally gleaned from surviving documents. We merely learn in passing that he not only appreciated fine cuisine, but also tobacco and alcoholic drinks such as beer, “Leipziger Gose” (a special local brew), “Hefen Brandewein” (a type of brandy), and various types of wine and was anything but an abstainer. It appeared that he once placed an order for 4 casks and 13 flagons of Rhine wine for the impressive sum of 84 thalers and 16 pennies, probably on the occasion of his marriage to Anna Magdalena. His wife also took a great interest in the vegetable garden and was fond of blue carnations and brightly colored songbirds.

“Everyone found him very pleasant and exceedingly interesting to talk to”

The companionable married couple was well known for their admirable hospitality, accommodating numerous visitors in their house. Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach recalls his sociable father who seldom wrote letters due to lack of free time, but used every opportunity “to talk volubly to honest folk, as his house was strongly reminiscent of a busy dovecot. Everyone found him very pleasant and exceedingly interesting to talk to. As he never touched on topics connected with his own life, the lack of knowledge on this subject is unavoidable.”

Several letters of recommendation testify to the great efforts Bach expended to advance the careers of his sons and pupils. A letter to a friend who was councilor in Sangerhausen reveals Bach’s paternal solicitude and warm-hearted efforts on the part of his “unfortunately wayward son”, the intelligent but unstable Johann Gottfried Bernhard Bach. We can thank Bach’s sense of family and pedagogical skills for the volumes of keyboard music created for his elder sons and Anna Magdalena. He must have been a loving husband and family man.

Surviving documents provide little information on his light-hearted, cheerful side. Far more interesting are the compositions revealing his humorous character; these include the so-called “Wedding Quodlibet” (BWV 524) with its numerous figures of speech and occasionally coarse and even frivolous ribaldry from Bach’s early period, the highly entertaining “Coffee Cantata” Schweigt stille, plaudert nicht (BWV 211) and the “Peasant Cantata” Mer hahn en neue Oberkeet (BWV 212) as a hereditary homage for Carl Heinrich von Dieskau originating in the spring of 1742 – a highly entertaining late work penned by the Cantor of St Thomas who titled the composition a “Cantate burlesque” (comic cantata).

Ribal elements and tavern songs

Bach and his librettist Christian Friedrich Henrici (alias Picander) employ an unbelievable quantity of irony, esprit and ambiguous wittiness in their lampooning of local circumstances, i.e. the feudal estate at Kleinzschocher (near Leipzig), even occasionally utilizing Upper Saxon dialect. The new “Oberkeet” (authorities), the “vortreffliche” (admirable) Chamberlain and his gracious wife must have listened to the performance of the humorous composition with its variety of ribald elements in text and music with somewhat forced smiles. Dancing and free beer rounded off the merry manifestation of loyalty for the new owner of the estate and the perplexed local priest too surely observed the frolicsome goings-on with a somewhat pinched expression. An exuberant pot pourri overture performed in the typical village instrumentation of violin, viola and double bass featuring popular melodic quotes (from popular street songs and tavern songs) were some of the new elements in Bach’s last documented secular composition. He would however have been betraying himself if he had dispensed with truly artistic movements such as the charming soprano aria “Klein-Zschocher müsse, so zart und süße”. As is the case with Mozart’s Musikalischer Spaß, certain allusions in Bach’s cantata will probably never be deciphered.

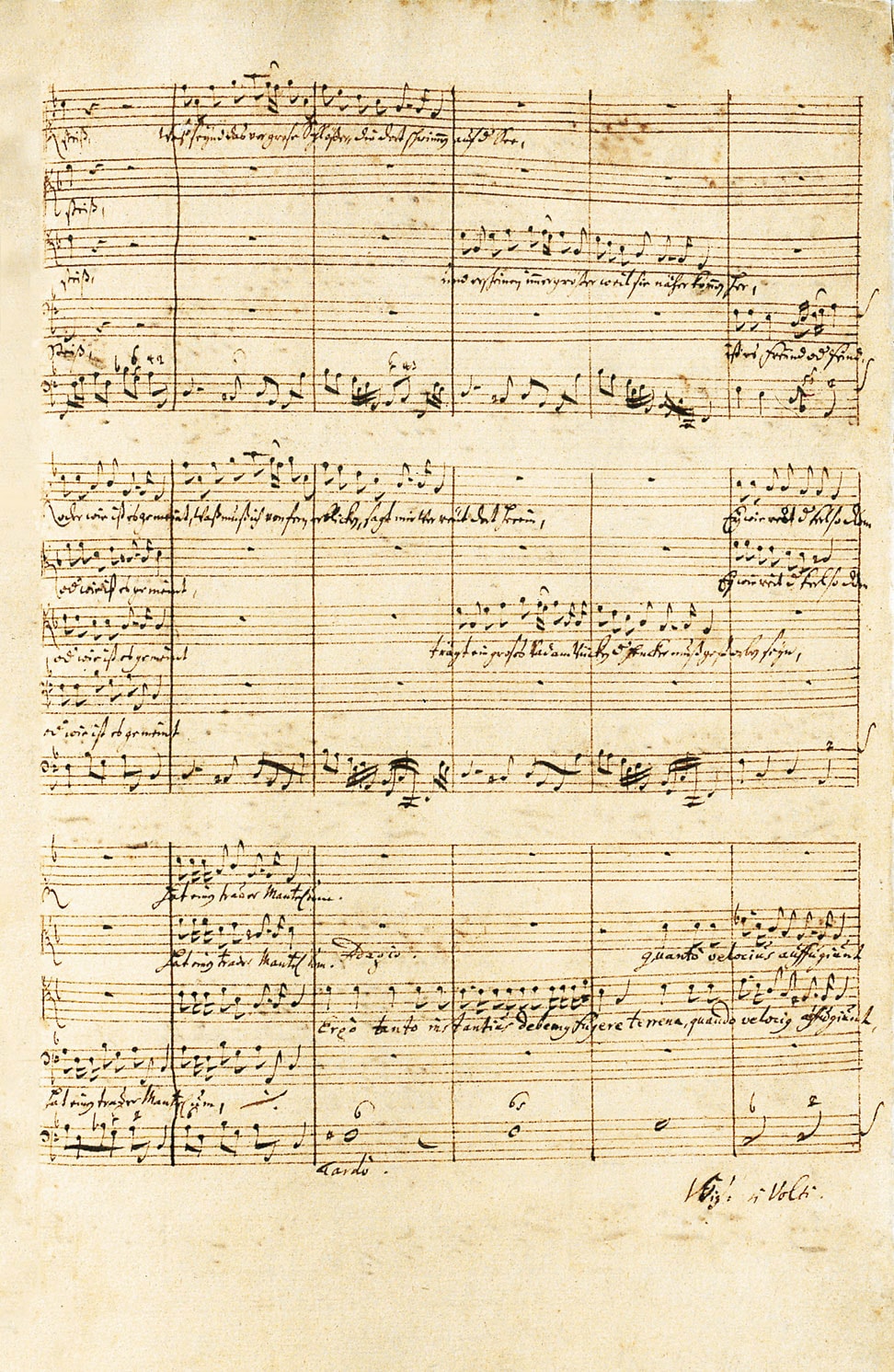

What does Bach’s Christmas Oratorio have to do with Hercules? More than you might think at first glance. Most of the choruses and arias in the cantata are familiar today through their incorporation by Bach into his later Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248. For example, the festive opening chorus “Lasst uns sorgen, lasst uns wachen” (Let us watch him, let us guard him) forms the opening chorus “Fallt mit Danken, fallt mit Loben” (Bow ye, thankful, kneel and praise ye) of the New Year’s cantata.

What does Bach’s Christmas Oratorio have to do with Hercules? More than you might think at first glance. Most of the choruses and arias in the cantata are familiar today through their incorporation by Bach into his later Christmas Oratorio, BWV 248. For example, the festive opening chorus “Lasst uns sorgen, lasst uns wachen” (Let us watch him, let us guard him) forms the opening chorus “Fallt mit Danken, fallt mit Loben” (Bow ye, thankful, kneel and praise ye) of the New Year’s cantata.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!