Sensual in the noblest spirit

Josef Gabriel Rheinberger’s Musica Sacra

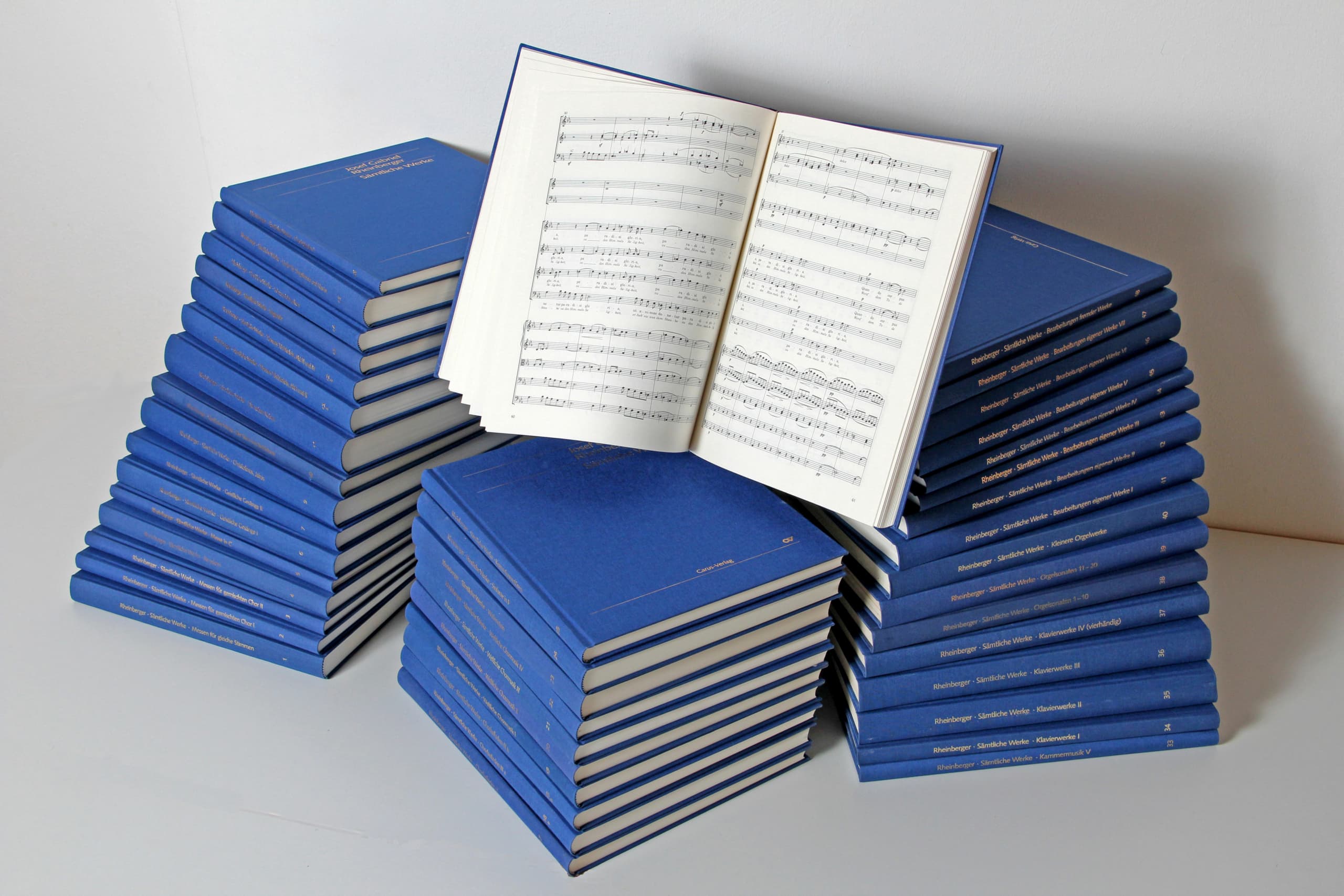

Church music was particularly dear to the Liechtenstein composer Josef Gabriel Rheinberger. But he was not a follower of the prevalent Cecilianism movement of his time. He strove instead for emotional warmth and sensuality in his musical language, rather than serene austerity. In his works he found his own individual sound, combining traditional structures with tension-laden harmonic writing in equal measure.

Munich, 9 March 1855: In a small room in Müllerstraße Josef Gabriel Rheinberger, shortly before his 16th birthday, a private student with a brilliant final diploma, but still without a paid position, composes a motet which is now one of his most famous works: the Abendlied (Evening Hymn) “Bleib bei uns.”

“In general I have more inclination and talent for church compositions than others,” wrote the young Rheinberger to his parents back home in Vaduz on 14.12.1953 . It was no empty phrase written simply to please his devout parents. It was the guiding principle for a career which, after long years as chief conductor of the Munich Oratorio Society and Professor at the Royal Conservatoire of Music, culminated in 1877 in his appointment as court Kapellmeister for church music by King Ludwig II of Bavaria.

Abendlied

Kammerchor Stuttgart, Frieder Bernius

CD Carus 83.113

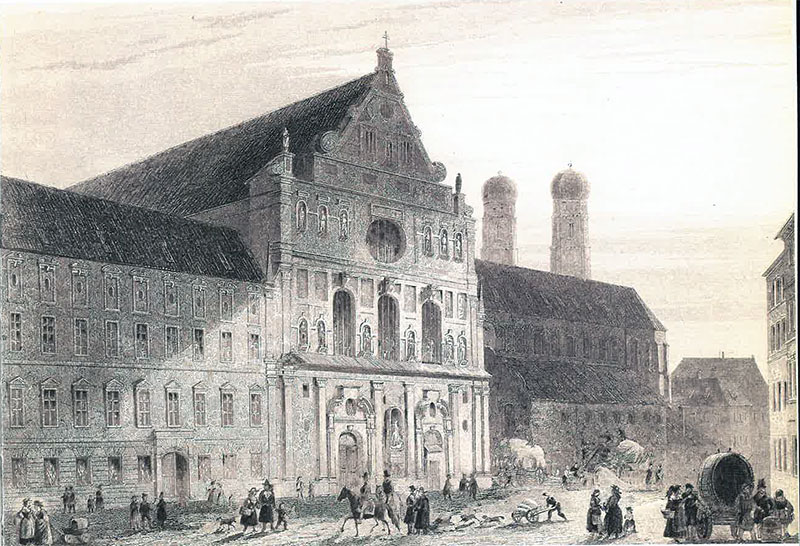

Anyone at this time who held one of the key positions in church music was almost inevitably drawn into the discussion about the duties and nature of church music, on which feelings had run high since the beginning of the century. Munich was one of the centers of Catholic church music reform and was a focus of attention for the representatives of the Cecilian movement, some of whom were extremely backwardlooking. They wanted to keep church music pure from developments in contemporary music and the operatic style, and favored pale imitations of Palestrina. In addition to this they rejected orchestral masses and condemned omissions or the changing of the word order in liturgical texts, as well as the singing of different sections of text at the same time.

Rheinberger, however, did not want to be forced into a rigid mould characterized by pure imitation. Although he too felt that church music should be serious and dignified, he also felt that it should neither be restricted to one particular style nor should it forego the harmonic or tonal styles of one’s own era. In 1888 he wrote to Franz Xaver Witt, the leader of the Cecilian movement in Regensburg: “It would not occur to any poet to write in the dialect and language of an earlier century and to proclaim this as the one and only correct poetry; for everyone, and that also includes artists working for the church, gives expression, based on immutable rules, to the feelings and views of his day and with the artistic means of his time.” He explained further that music worked sensuously, like all art, and that it was the duty of a church artist “that it [the music], however, works sensually in the noblest spirit.”

A major part of Rheinberger’s sacred music can be understood with this in mind. As a church composer he based his work on the “immutable rules,” the rules of counterpoint, as understood by the old masters, but at the same time he used the “artistic means of his own time,” such as tension laden modulations and sounds heightened through chromatic alteration. Yet the individual effects never draw attention to themselves, but are always subordinated to the overall effect of a work, which is characterized by mainly songlike melodic lines and a well balanced harmonic development. The result of this middle way for the listener is undoubtedly what Rheinberger understood as church music which is “sensual in the noblest spirit.”

Practically as a “statement,” around 1877 Rheinberger composed a series of works which impressively substantiate his position. These include the Cantus Missae op. 109, an eight-part unaccompanied mass ostensibly composed in the “old style” and yet shaped using the harmonic means of the time. It was dedicated to Pope Leo XIII. Rheinberger dedicated the Fünf Motetten (Five Motets) op. 107 (including Christus factus est with its impressive fugue) to the St. Thomas Choir, Leipzig, for in Bach’s music he saw a counterbalance to Catholic attempts to restore the music of Palestrina and his contemporaries.

As well as ambitious four to six-part motets (including the magnificent, contrapuntally dense and sensuous motets opp. 133 and 134 and the Hymnen op. 140 for choir and organ) Rheinberger also specifically composed “easy-to-perform” works, including the Mass in G major op. 151 and the Stabat Mater op. 138 for chorus, organ and strings.

Kammerchor Stuttgart, Frieder Bernius

CD Carus 83.113

CD Carus 83.140

He wrote thirteen masses and three Requiem settings, although in later years he increasingly turned to the organ accompanied mass. The most popular masses include not only the Mass for female voices in A major op. 126, but also the two masses for male voices opp. 172 and 190 dating from the 1890s. The Mass in G minor op. 187, which Rheinberger dedicated in 1897 to the memory of Johannes Brahms, is also one of the high points of his output, as are the two original cycles for solo voice and organ op. 128 and op. 157. As a counterbalance to his liturgical masses for small forces, Rheinberger composed the Mass in C major op. 169 for chorus and orchestra in 1891.

Many sacred works for the concert hall date from Rheinberger’s period as director of the Munich Oratorio Society. This was where works such as the Hymn Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen op. 35, the Passionsgesang op. 46 in simple folk style and in particular the large scale Requiem in B flat minor op. 60 composed earlier in 1870 were performed. Rheinberger’s two oratorios were composed to texts by his wife Fanny: the legend Christoforus op. 120 (1882), which enjoyed tremendous success both in Germany and abroad during his lifetime, and the Christmas cantata Der Stern von Bethlehem (The Star of Bethlehem) op. 164 (1890).

- Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen

Kammerchor Stuttgart, Frieder Bernius

CD Carus 83.113

- Passionsgesang

Vancouver Cantata Singers, James Fankhauser

CD Carus 83.146

- from: Der Stern von Bethlehem,

Chor des Bayerischen Rundfunks,

Symphonie-Orchester Graunke, Robert Heger

CD Carus 83.111

On 25 November 1901 Rheinberger died in Munich. In his last weeks he had worked on a mass which he wanted to call the “Allerheilige Messe” (Mass for All Saints). His compositional sketches for opus 197 went as far as the end of the Credo; he only notated the opening measures of the Sanctus and Agnus Dei. The complete fair copy of the full score admittedly breaks off in the middle of the Credo. Rheinberger only wrote out the soprano part on the page, just up to the words: “passus et sepultus est. Et resurrexit tertia die secundum scripturas.”

Kyrie from Rheinberger’s last work, the Mass in A minor

KammerChor Saarbrücken, Georg Grün

CD Carus 83.410

We gratefully acknowledge the Amt für Kultur, Liechtensteinisches Landesarchiv Vaduz, Josef Rheinberger-Archiv for permission to use the following images:

Banner: Birthplace, detail of a drawing by Anton Rheinberger, LI LA RhAV E 18/004

Photo of the 16-year old Rheinberger, dated 13 March 1855 (by Erwin Hanfstängl), LI LA AFRh Z 2/28

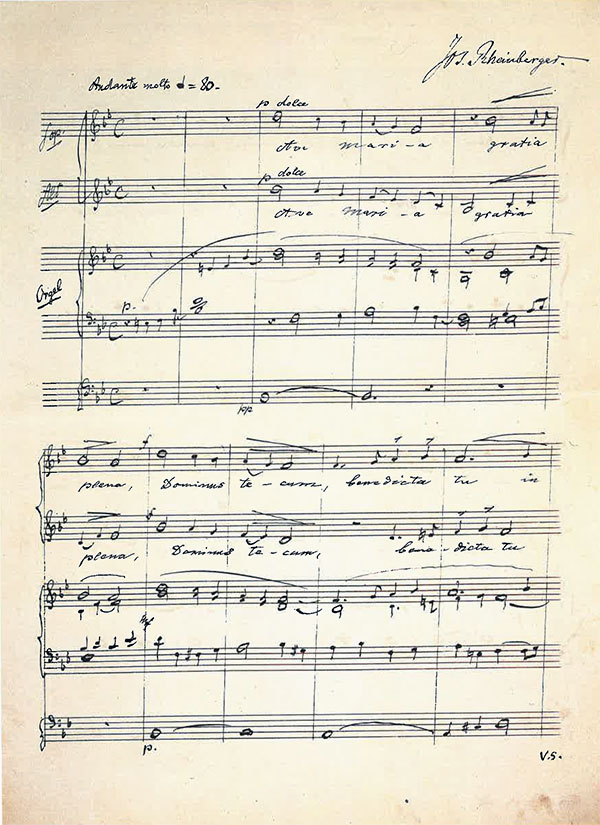

J.G. Rheinberger, Ave Maria, autograph score of WoO 7, No. 1. LI LA RhaV E 18/189

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!