The Requiem – and what else?

Guiseppe Verdi’s vocal church music

The Messa da Requiem is truly Verdi’s most impressive work, but due to the size of the needed ensemble it can hardly be performed. Besides this milestone, Verdi created a few other sacred works.

It must have been an impressive experience when Giuseppe Verdi’s Messa da Requiem was first heard in the Church of San Marco in Milan on May 22, 1874. More than 200 choral singers and instrumentalists filled the huge church with music, taking great care in exploring the entire spectrum of the tonal extremes of the score with its four-part horn section (ranging from the piccolo in the highest register to the ophicleide in the lowest register).

The composition had emerged from the failed project of the Messa per Rossini with which Verdi and twelve of his Italian fellow composers intended to memorialize Gioacchino Rossini who had died in 1868. Verdi´s contribution to this work, a musical rendering of the concluding responsory Libera me, then became the cornerstone of his own complete Reqiem setting which he began working on in 1873. He had his publisher Giulio Ricordi send him “French music paper of excellent quality, thick and sharply lined” and filled a total of about 400 pages with the transcription of the score. By April 1874, the last part of the manuscript, the Offertorio, was completed. The vocal score and the instrumental parts had already been drawn up but the choir rehearsals had not yet begun. Since women were not allowed to sing in church, the search for a suitable performance venue turned out to be difficult. Likewise, the participation of an orchestra was not allowed there. Eventually, it was agreed upon that the two soloists of the premiere, Teresa Stolz and Maria Waldman, as well as female choral singers would be wearing a veil and perform from behind some kind of lattice.

Julia Rosemeyer has been an editor at Carus-Verlag since 2006, with particular responsibility for Urtext editions like Verdi’s Requiem.

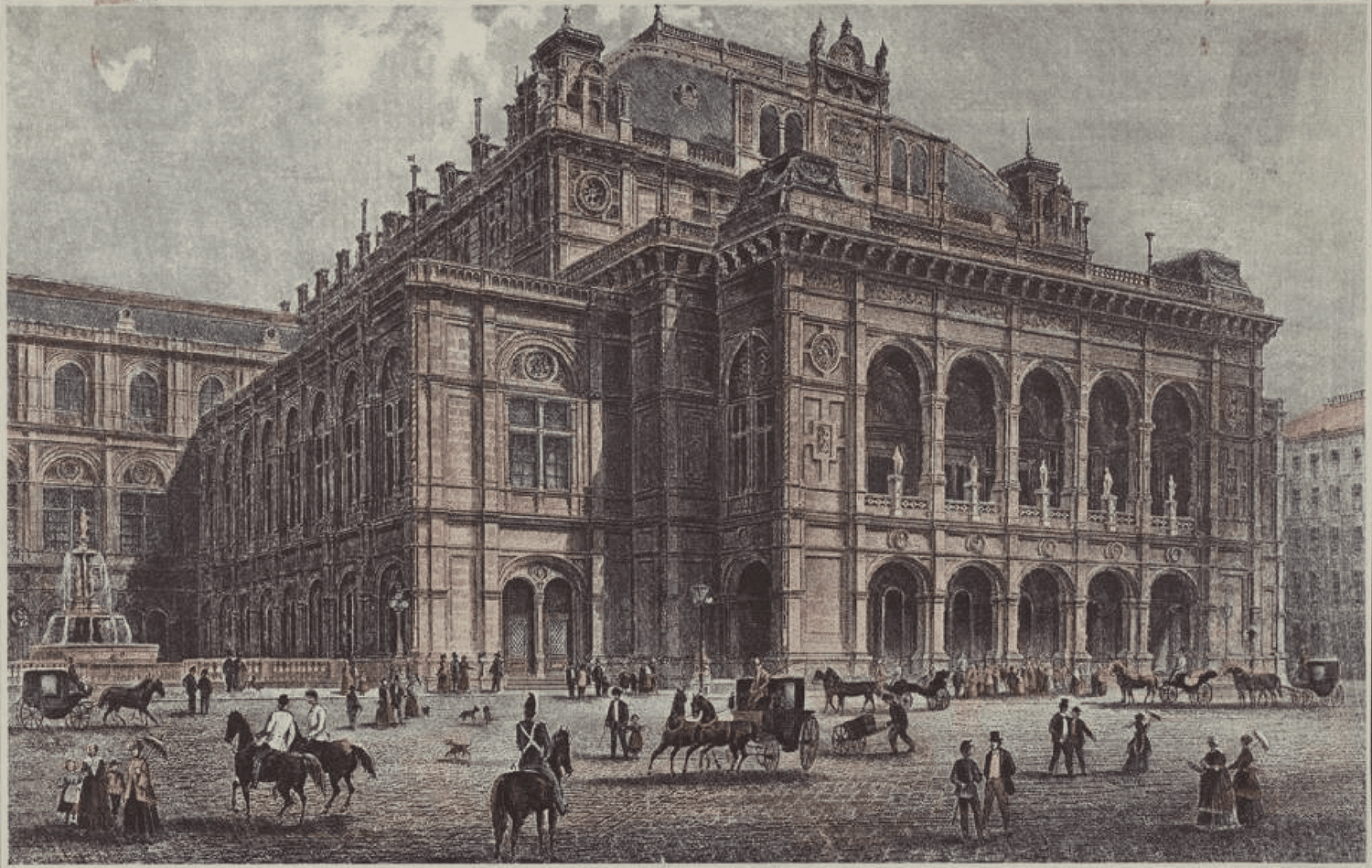

The San Marco performance was followed by further perfomances directed by the composer and taking place at La Scala in Milan, the Opéra Comique in Paris, the Royal Albert Hall in London, and the Court Opera House in Vienna. (Johannes Brahms attended one of the performances in Vienna.) That the German and Italian interpretations of church music differed greatly at that time is revealed by a comment by Eduard Hanslick on the occasion of the 1875 performances in Vienna:

“What in Verdi’s Requiem may seem too passionate, too sensual, emerges straightforwardly from the manner of feeling of his people and, after all, shouldn’t the Italians have the right to ask whether they may speak Italian to God?”

(Musikalische Stationen, Verdis Requiem, Berlin 1880, p. 5).

However, to this day the extensive instrumentation of the Requiem has proved to be problematic. For this reason, two arrangements have been published by Carus which make the work performable for smaller choirs and consolidate the instrumental forces. The one by Joachim Linckelmann for chamber orchestra reduces the wind instruments to seven single parts and provides alternatives for the use of the “distant trumpets” (Ferntrompeten). In his arrangement, Michael Betzner-Brandt goes even further by arranging the orchstestral part for a five-piece ensemble (consisting of piano, horn, double bass, marimba (+ gran cassa), and timpani), with the marimba in particular – being a true “sound acrobat” – imitating a variety of instrumental timbres. By using humming voices, the choir also takes on some of the parts of the Dies irae (string or woodwind adaption for “Quid sum miser” and “Lacrimosa”).

Apart from this piece, which is a milestone in the history of music, Verdi created only a few works of sacred music.

In his youth he wrote an almost forgotten Messa di Gloria (around 1833) and a Tantum ergo (1836) for tenor solo, orchestra and organ which he composed even prior to his first opera and performed in the church of San Bartolomeo in Busseto. Verdi later distanced himself from these early works, and didn’t write any more church music until his advanced age.

Giuseppe Verdi Messa da Requiem

- Full Score: Carus 27.303

- Carus Choir Coach: Carus 27.303/91

- App: Carus 73.313

In his operas, however, we find numerous references to religious contexts as well as scenes set in churches or monasteries. Time and again he has his protagonists raise their voices to God, mostly in situations of great danger. One example of these arias which stand in the tradtition of the preghiera (Italian for “prayer”) is Lida’s aria “Deus meus – O tu che desti il fulmine” for soprano, choir and orchestra from the opera La battaglia di Legnano.

Pater noster for five-part a cappella choir and Ave Maria for solo soprano and strings were written after a lengthy creative break, apparently without any external reason. They were premiered together in 1880 at a concert on the occasion of the ceremonial unveiling of a bust of Verdi in the foyer of La Scala in Milan. The expansion of the title by the words “volgarizzato da Dante” indicates that they were based on Italian translations of the Latin liturgy, but this attribution to Dante Alighieri (1265–1321) has turned out to be a mistake. In both cases, the meter used is the hendecasyllable (“eleven syllables”) (“O Padre nostro, che ne’ cieli stai“ and “Ave regina, vergine Maria” respectively). Pater noster demonstrates Verdi’s knowledge of classical vocal polyphony which he enriched with the harmonic liberties of the 19th century. (He even insisted on publishing them with old clefs!) Ave Maria – not to be confused with the movement of the same name from the Quattro pezzi sacri – was initially published only as a vocal score and was therefore mostly performed on piano until the 20th century, as a result of which the pronounced treatment of the strings (including the division of the cellos into three parts) was lost.

Giuseppe Verdi Messa da Requiem

- Arrangement for small ensemble (arr. M. Betzner-Brandt): Carus 27.303/50

- Arrangement for chamber orchestra (arr. J. Linckelmann): Carus 27.308

The very name Quattro pezzi sacri (Four Sacred Pieces) makes it clear that similar things have been put together here – similar in terms of the sacred character of the pieces, without them having been conceived as a cycle or having a uniform instrumentation. The two solo a cappella compositions (Ave Maria and Laudi alla Vergine Maria) and the two larger movements with orchestral accompaniments (Stabat Mater and the double-choir Te Deum), which are most frequently performed today, were written independently of each other between 1889 and 1897. At the request of Verdi’s publisher Ricordi, they were published together in 1898 after a revision.

In Ave Maria for four mixed voices, a study of the “enigmatic” scale, a Latin text is set to music, whereas Laudi alla Vergine Maria (Hymn to the Virgin Mary) for four female voices once again uses an Italian, non-liturgical text, this time actually by Dante Alighieri. The genesis of Te Deum and Stabat Mater, Verdi’s last two works, may be related to the imminent death of his wife Giuseppina. Despite their wide dynamic range, they have a rather contemplative, intimate character. Verdi is said to have handed over the manuscripts for printing “with immeasurable pain” and to later have asked that the score of the Te Deum be placed in his grave.

Giuseppe Verdi Quattro pezzi sacri

Carus 27.500

Finally, among the album leaves there is another late work with a liturgical reference, “Pietà, Signor, del nostro error profondo” for soprano and piano (1894). It is based on a text by Verdi’s librettist Arrigo Boito (1842–1918) which relates to the Agnus Dei of the Mass Ordinary.

With the Quattro pezzi sacri, a circle is completed in Verdi’s late œuvre. At the end of his life he returnes to church music which had been the starting point of his musical activities when he was appointed as organist at the village church of Le Roncole at the age of twelve.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!