Bach’s “other” St. John Passion from 1725

A small plea for a great Passion music

The St. John Passion was performed under Bach’s direction in Leipzig at least four times, but each time in a different form. And not all versions survive complete, so decisions need to be made for each performance nowadays. Increasingly the 1725 version with the opening chorus “O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß” is performed. The omission of “Herr, unser Herrscher” in this performance version is coupled with new discoveries. We hear the part of the evangelist as it was sung back then in Leipzig. In addition, highly dramatic arias such as “Himmel reiße, Welt erbebe” are heard to their best advantage.

The St. John Passion preoccupied Bach for many years: from his first Leipzig Good Friday in 1724 to his second-last or even his last year of work and life. This has led to a virtual multiplicity of surviving copies of the work. What we are presented with is not a single Bach score with the individual instrumental parts. On the contrary, over 700 pages of music have survived dating from the period between 1724 and 1749. Alongside the composer, a further 20 copyists were involved in this project! And some of the pages of music used in Bach’s performances in Leipzig have long been lost.

Let us first look at the textual form of the work. The impression of a colorful mixture is thrust upon us, for the Passion narrative from the Lutheran Bible together with the chorale verses are interspersed with aria texts of very varied origins. An unknown editor compiled these in 1724 from several sources of poetry. He took verses from the famous Passion story by Barthold Hinrich Brockes, the Hamburg city councillor, and other sources. A few of the aria texts, such as “Ich folge dir gleichfalls mit freudigen Schritten” were probably written by this editor who was particularly inspired by the basic ideas of the fourth Gospel. All-in-all, the varied pasticcio character of the libretto distinguishes the St. John Passion from its companion work the St. Matthew Passion with its text by a single author Picander whom Bach named on the title page of his fair copy.

Johann Sebastian Bach

St. John Passion BWV 245

version II (1725)

scoring: Soli SATBB, Coro SATB, 2 Fl, 2 Ob (Obda), 2 Obdaca, Vga, 2 Vl, Va, Bc

duration: 120 min

If we continue the comparison of the two works, further striking differences are apparent. Firstly, the St. John Passion lacks a final version. It was performed under Bach’s direction at least four times in Leipzig, each time on Good Friday in 1724, 1725, 1732 (?), and 1749 (and possibly also 1750). But each time the work was performed in a different form. A “final version authorised by the composer”, such as we know with the St. Matthew Passion, does not seem to exist. And this again becomes particularly clear with the fair copy of the score (1739). Only the first 20 pages of this St. John Passion score – up to shortly before the chorale “Wer hat dich so geschlagen” – were written by Bach and document a revision of the work. Then, however, the handwriting changes, for a copyist engaged by Bach later added the other movements based on the original score of 1724 which was then still to hand but has since been lost.

How is this to be explained? Bach probably planned a performance of his St. John Passion around 1739 which may not have come to fruition. At any rate there is a note about a ban on Passion performances that year. All this could explain the fact that Bach broke off the revision after 20 pages of score. In addition, he never transferred the numerous alterations already made in the first movements into his set of parts. Consequently, numerous details we hear in modern performances of the St John Passion, for example in the first half hour, were never heard in performances conducted by Bach! These include the passing notes in the middle parts of the first two chorale verses and above all the distinctive major third at the end of the first chorale “O große Lieb” on the word “leiden” (suffer). With all of Bach’s performances, this chorale ended rather restrainedly in the minor key. Only in the 1739 score not used by Bach in his own performances, do we find a B natural rather than a B flat in the tenor part.

But why did Bach perform the St. John Passion two years in succession? This question can only be answered with hypotheses. Perhaps he had initially planned a completely new setting of the Passion in 1725 as an integral part of his cycle of chorale cantatas. It is well known that this cycle terminated prematurely around Easter 1725, so Bach might have changed his original plan for a Passion setting or even had to abandon it completely. Was the sudden death of his chosen librettist possibly responsible for this, the fact that a planned libretto no longer came to fruition? And did the young theology student and Bach pupil Christoph Birkmann (1703–1771), whom Christine Blanken has identified as the librettist of many Bach cantatas (Bach-Jahrbuch 2015), perhaps assist the Kantor of St. Thomas’s in spring 1725 in arranging this Passion libretto, which he later published in Nuremberg under the title “Das schmählich- und schmertzliche / Leiden / Unsers Herrn und Heilandes / Jesu Christi / in einem / Actu Oratorio / besungen”?

carus plus

For J. S. Bachs St.John Passion (version IV resp. traditional version) innovative practice aids are available: The work is available in carus music, the choir app, and in the series Carus Choir Coach, practice CDs.

These offer choir singers the unique opportunity to study and learn their own, individual choral parts within the context of the sound of the entire choir and orchestra.

The result, however, is two Passion settings by Bach from 1724 and 1725, which differ from each other considerably. Characteristic of the 1725 Passion is the framing of the work with two great chorale settings: “O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß” as the Exordium and “Christe, du Lamm Gottes” as Conclusio. Additionally, Bach newly incorporated several arias into the work. It is unclear at present whether these originated from an older setting of the Passion by him – possibly composed in 1717 for a performance at Schloss Friedenstein near Gotha – or whether Bach newly composed them in 1725 to texts by Christoph Birkmann. With regard to church music and concert practice after Bach’s death, it is certain that the entire performance tradition of the St. John Passion – from the 19th century to Arthur Mendel’s edition as part of the Neue Bach-Ausgabe (1973) – does not correspond with any of the four versions by Bach.

In point of fact, the 1739 score (movements 1–10) has been mixed with Versions I and IV (the other movements). The reasoning behind this, at least according to Mendel, is the understandable desire that each movement of the work should be heard in its most fully-developed version. But this has its price and overall results in a form of the work which Bach never performed.

But why do we not perform one of the authentic Bach versions of the St. John Passion? The difficulty is that none of the four versions survives in a sufficiently complete state. The first and third versions can only be reconstructed with difficulty because of lost original music material. Version II (1725) and version IV (1749) are, however, performable. And the second version is probably the least well-known major vocal-instrumental work of Bach to this day!

In this Passion setting, Bach devoted himself especially to the two opposite poles of devotion and opera, combining them in a unity laden with tension. A total of 18 verses of chorales represent the liturgical aspect, whereas the newly-incorporated arias focus on a highly dramatic and therefore operatic style. With the chorale verses, what is most striking is the variety of styles of composition, ranging from typical four-part “Bach” writing to arias with underwoven chorale verses. And finally, Bach would not be Bach if he only treated contrasting themes one after another rather than integrating them simultaneously by means of musical and theologically rich, indeed almost “intricate”, overlayering.

As regards the part of the Evangelist and the words of Christ, the second (and first) version of the work is simpler in the opening “scenes” than the revised version of 1739. In the early versions the two high notes on top A at the word “Hohenpriester” are missing. And with the Vox Christi, Bach only wrote the arioso-like accompaniment of the continuo to the intensively repeated words “den Kelch, den mir mein Vater gegeben hat” in 1739. Perhaps this is even a brief reminiscence of the companion setting of the already existing St. Matthew Passion, in which the recitatives of the Vox Christi – and also the words of Communion which are not included in St John’s Gospel – are accompanied by the strings.

J. S. Bach

St. John Passion

Version IV (1749) / traditional version

The fourth and final version which was performed under Bach’s direction in 1749. At the same time, with the aid of the appendix it is possible to perform the work in the traditional “mixed version”, please use for the “mixed version” (vocal score Carus 31.245/93)

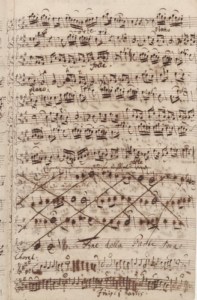

The second version of the St. John Passion was also not the final one. Everything in fact points to the fact that Bach never arrived at a definitive form for this work. So his experimenting is all the more revealing, as can be seen on a page from the first violin part (click on the image to magnify; copied violin I part. Staatsbibliothek Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung mit Mendelssohn-Archiv, Mus. ms. Bach St 111).

The second version of the St. John Passion was also not the final one. Everything in fact points to the fact that Bach never arrived at a definitive form for this work. So his experimenting is all the more revealing, as can be seen on a page from the first violin part (click on the image to magnify; copied violin I part. Staatsbibliothek Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Musikabteilung mit Mendelssohn-Archiv, Mus. ms. Bach St 111).

This page was played from in all four of Bach’s performances between 1724 and 1749, but each time somewhat differently! On the first eight staves is the conclusion of the tenor aria “Ach, mein Sinn”, as found in Version I (1724). When Version II was performed the following year, this aria was omitted; therefore it is in parentheses and furthermore, there is a reference for Bach’s musicians to the inserted sheet with the aria “Zerschmettert mich” which was now to be played. The following chorale “Petrus, der nicht denkt zurück”, which ends the first part of the Passion in all four versions, is in A major in Versions I and II. For Version III (1732) Bach altered the key by erasing two accidentals and overwriting the notes in G major. However, when he reversed this alteration for the fourth version (1749), the renewed overwriting made the legibility even less clear. He therefore crossed out the chorale with thick diagonal pen strokes and notated it below – and here we see the clumsy manuscript writing of Bach’s old age – once more in the original key. Perhaps in order to prevent misunderstandings, Bach again entered the marking “Finis I Partis”. Despite these repeated alterations, the performers at least needed to know that the sermon definitely followed here.

A brief overview (see box) clarifies the “structure” for the second version of the St. John Passion. In five places, a movement has been eliminated from Version I and a new one inserted in its place. With “Himmel reiße, Welt erbebe” an additional aria is inserted into the work, independently of any deletion.

| Version 1 – 1724 | Vesion II – 1725 |

|---|---|

| Satz 1: “Herr, unser Herrscher” | Satz 1: “O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde groß!” |

| – | Satz 11: “Himmel reiße, Welt erbebe” (nach: “Wer hat dich so geschlagen?”) |

| Satz 13: “Ach, mein Sinn” | Satz 13: “Zerschmettert mich” |

| Satz 19: “Betrachte, meine Seel” und Satz 20: “Erwäge” | Satz 19: “Ach, windet euch nicht so” |

| Satz 33: dreitaktige Kurzfassung (verschollen, nach Markus 15,38) | Satz 33: “Und der Vorhanhg im Tempel” (sieben Takte, nach Matthäus 27,51f.) |

| Satz 40: “Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein” | Satz 40: “Christe, du Lamm Gottes” |

It is very unlikely that Bach was dissatisfied with either his old or new settings of the St. John Passion on Good Friday 1725. Perhaps he found their reception aspect interesting; whether and when his listeners would notice that – despite the new chorale framework and substituted arias – much music from the previous year was being played. The further Leipzig history of the St. John Passion is highly unusual. Although the work already existed in two versions in 1725, it became almost a work for experimentation in Bach’s Passion music as none of the movements newly introduced in 1725 remained in the work for long. But we are aware of the peaceful coexistence of versions with Bach from other work groups. The image of the St. John Passion remains a colorful and shifting one, because Bach “only ever gave it a current form, and never a final one” (Hans-Joachim Schulze). Even Version IV once again demonstrates how much the composer was open to innovations, for example with regard to the basso continuo and the orchestration, and how, on the other hand, ironically with the last version he clearly strove to return to the direction of the first form of the work of 1724, from which he had distanced himself furthest with Version II.

Bach research has taken a long time to allow the St. John Passion to be regarded as a work in four different complete versions, yet at the same time as an incomplete work. About fifty years ago, scholars succeeded in arriving at an unambiguous order for the 700 pages of music mentioned at the beginning into four performances given by Bach. But only in 2004 did Peter Wollny’s edition for Carus-Verlag enable the second version of this Passion music setting to be performed as it was heard on the afternoon of 30 March, Good Friday 1725, in St Thomas’s Church. This “other” setting of the St. John Passion by Bach is still very worthwhile hearing for connoisseurs and music lovers today.

I just completed my first hearing of the St. John Passion 1725 performed by The Netherlands Bach Society. I was pleased, but very stunned at how different it sounded to me, I thought, “Surely something is amiss; where is that ponderous opening chorus that always gives me chills etc.” It was only after the performance that I came upon your tremendously informative explanation that are at least four versions of this Passion!!! I devoured your scholarship with relish. Now, I will return and re-listen anew to the same performance paying particular attention. Thanks for such a completely engrossing article. Much thanks. Brian Kerr

Hi Brian, that’s great to read, thanks so much for the wonderful feedback!