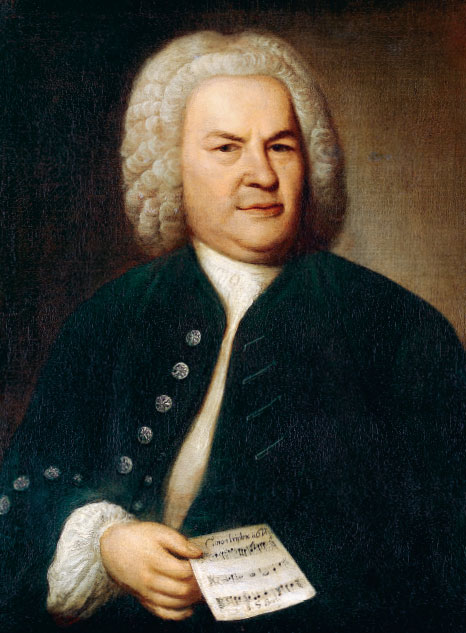

“Hochfürstl. Sächsisch-Weißenfelsischer würklicher Capellmeister”

Johann Sebastian Bach and Duke Christian of Saxe-Weissenfels

Johann Sebastian Bach’s secular cantatas provide an exciting insight into his activities between city and court, between the beginning of the Enlightenment and absolutism. Activities which probably characterized a successful life back then, but seem slightly strange to us now, perhaps even disconcerting. Uwe Wolf has researched the circumstances surrounding the composition of Bach’s wonderful Hunting Cantata, and went on the trail of Bach in Weissenfels. Come along with us!

It was a momentous and unusual decision by Elector Johann Georg I of Saxony (1585–1656, significant in the history of music as a patron and employer of Heinrich Schütz, amongst other activities): in his will, he decreed the establishment of secundogeniture principalities for his second and subsequent, or posthumously-born sons. So, after his death in 1756 three partially sovereign principalities were created in the Electorate of Saxony: Saxe-Weissenfels, Saxe-Zeitz, and Saxe-Merseburg. These could be bequeathed further to descendants in the direct line of succession, but after the direct line died out they were to revert to the Electorate of Saxony (this was then the case between 1718 [with Zeitz] and 1746 [with Weißenfels]).

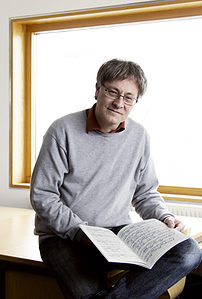

As a musicologist, Dr. Uwe Wolf is particularly at home in the 17th and 18th centuries. The focus of his work ranges from the time of Monteverdi and Schütz to Bach and the generation of Bach’s sons and pupils through to Viennese Classicism. He has been head of the editorial department at Carus-Verlag since October 2011. Prior to this, he worked in Bach research for over 20 years.

Culture instead of foreign policy

The politically unimportant secundogeniture principalities each sought their own ways of displaying their absolutist splendor. The Dukes of Saxe-Weissenfels participated in the “rivalry between the royal capitals” especially in the cultural field. They endeavored to create a reputation for the court through its cultural activities, something which eluded it in the political sphere. The construction of Neu-Augustusburg Castle was one such activity, coupled with a generously-staffed court ensemble, and magnificent court festivities full of music performances.

Weißenfels an der Saale, approx. 1900

Neu-Augustusburg Castle towers over the city

But none of the Dukes of Saxe-Weissenfels carried the sumptuous upkeep of the court to such excesses as Duke Christian, who ruled from 1712–1736. Just a few years after Christian came to power this led to the financial collapse of the duchy; an imperial debt commission was created, but only after Christian’s death was there an end to the courtly splendor.

Duke Christian, patron of the fine arts

However financially unwise Christian’s overstepping the mark was, his period of rule was extremely fruitful in cultural terms. The culmination of the sovereign prince’s displays of splendor were the court festivities, of which the celebration of Duke’s birthday on 23 February took pride of place. The festivities for Duke Christian’s birthday always stretched over two weeks, until 9 March. And music played a major role in these. In 1732, for example, we know that in the church service alone ten compositions were performed, some of them extensive. And wordbooks for a ‘Tafelmusik’, or ‘table music’, and three serenades survive – all extensive works (it’s not often that a serenade has 20 movements!). There are also references to the performance of an opera. The Tafelmusik and the serenades were gifts from individuals or groups of people, so unlike the church service these were not performances organized by the Duke.

Bach’s patron, Duke Christian

The Weissenfels court records contain some delightful correspondence which provides an insight into the reasons for such activities. The Leipzig scholar Johann Christoph Gottsched (1700–1766) was appointed an associate professor in 1730, but wanted a position as a full professor at Leipzig University. Since Christian, the Duke of Weissenfels, had an important say in the next appointment in Leipzig, Gottsched tried to enlist him for his cause, and in January 1733 turned to the Weissenfels court librarian Heinrich Engelhard Poley for advice.

Memorial plaques at Neu-Augustusburg Castle

Whilst Gottsched had a poem in honor of Christian in mind, Poley sought to convince Gottsched that a Tafelmusik or opera would be the right thing, and gave the poet the advice that he would do well to avoid the word “Wonne” (joy) and the rhymes “Sachsen” (Saxony), “Wachsen” (to increase) and “Achsen” (axes), as the Duke disliked these. But Gottsched stuck with his original plan and wrote a poem of praise for the 1733 birthday festivities (admittedly without the aforementioned rhymes!). The month remaining between Gottsched’s inquiry and the next birthday would surely have been too short for an opera. He evidently hit the right note, for the following year he was awarded the longed-for professorship.

Johann Sebastian Bach, Hochfürstl. Sächsisch-Weißenfelsischen würklichen Capellmeistern

Johann Sebastian Bach also sought Christian’s favors – with success: in 1729 he was awarded the title of court Kapellmeister which he also used widely. For example, on the title page of Part One of the Klavierübung BWV 825–830, printed in 1731 we read: “Clavir Ubung … von Johann Sebastian Bach[,] Hochfürstl. Sächsisch-Weißenfelsischen würklichen Capellmeistern und Directori Chori Musici Lipsiensis”. By acquiring the court title, Bach hoped to strengthen his position with the various Leipzig institutions, which were not always well-disposed towards him.

Three compositions by Bach for Christian’s court are known. These began with the well-known Hunting Cantata BWV 208, probably composed for the Prince’s birthday in 1713. During Bach’s Leipzig period, there followed the Shepherd Cantata “Entfliehet, verschwindet, entweichet, ihr Sorgen” (Fly, vanish, flee, O worries) BWV 249a for the Prince’s birthday in 1725 (the model for the Easter Oratorio) and “O angenehme Melodei” (O pleasing melody) BWV 210a on the occasion of Christian’s stay in Leipzig in 1729 (and other works may well have been composed for Weissenfels). The four well-known versions of BWV 210/210a are a perfect example of cantata recycling. Thus the beginning of the last aria is “Sei vergnügt, großer Herzog” (Be content, O great Duke; Christian of Saxe-Weissenfels), “Sei vergnügt, großer Flemming” (Be content, O great Flemming; Joachim Friedrich von Flemming, governor of Leipzig), “Seid vergnügt, werte Gönner” (Be content, esteemed patron; addressee unknown), “Seid beglückt, edle beide” (Be happy, noble pair; unknown bridal couple).

Bach’s Weissenfels “debut” in 1713 was probably not entirely the result of his own initiative; rather, he seems to have been commissioned (and remunerated) by his employer Ernst August, the Duke of Weimar. The libretto of the large-scale Tafelmusik was written by the Weimar court poet Salomon Franck (1659–1725), many of whose texts Bach later set to music. Bach himself travelled to Weissenfels with some of the Weimar court musicians to direct the performance in the hunting lodge, the present-day “Ringhotel Jägerhof”. The Hunting Cantata is, as far as we know, Bach’s first large-scale composition and is also his oldest surviving secular cantata.

As with some of Bach’s other secular cantatas (BWV 204, 210, 211), the Hunting Cantata begins straight away with a secco recitative. This is not only a somewhat unusual opening, it is also slightly unsuited to a Tafelmusik, because such a beginning would be drowned out in the general noise level. The cantata would certainly have been preceded by an instrumental piece which would draw the listeners’ attention to the music and at the same time introduce them to the atmosphere of the work.

Hunting lodge, today’s “Ringhotel Jägerhof”

A suitable piece would be the 1st movement of the 1st Brandenburg Concerto. There is an early version of this concerto, which cannot be precisely dated, and its composition has long been hypothetically associated with the Hunting Cantata; the scoring and key of both works fit almost perfectly together. And interestingly, Bach also used this first movement in the Leipzig cantata “Falsche Welt, dir trau ich nicht” [Treach’rous world, I do not trust you] BWV 52 as the introductory Sinfonia, and here too it was taken from the early version of the concerto! Of course we cannot be absolutely certain that this movement in fact preceded Bach’s 1713 Hunt Cantata, but it is a suitable movement presumably from the right period. In the new Carus edition of the Hunting Cantata this movement is therefore included as a suggestion for an introductory Sinfonia.

Recycling cantatas

Like many of Bach’s occasional secular cantatas, the Hunting Cantata also had a life after 1713: as a congratulatory cantata it was repeated almost unaltered, probably in 1716 at the Weimar court; “Chri-sti-an” became “Ernst Au-gust”, that was it. And in terms of text, another distinctly different version of the cantata survives (BWV 208a), which was performed later in 1742 on the name day of the Saxon Elector and Polish King August III.

Memorial plaques at the Jägerhof

It was August III who succeeded August the Strong as Elector of Saxony as Friedrich August II in 1733, and then as August III in 1734 also became Polish King, and for whom Bach wrote the Kyrie and Gloria of the Mass in B minor; again he hoped for a court title (the dedication of the Mass reads “Praedicat von Dero Hoff-Capelle”), which he was finally granted after a further request in 1736.

And Bach naturally included movements from this early and successful work in his sacred cantatas: we find two movements in the cantata “Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt” (So greatly God esteemed the world) BWV 68 for Whit Monday 1725, and another was included in the cantata “Man singt mit Freuden vom Sieg” (The voice of rejoicing and hope) BWV 149 for the Feast of St Michael from 1728 or 1729. We can also assume that other usable movements (that is arias and choruses) were re-used in cantatas by Bach which have not survived.

Bach’s secular cantatas offer a small insight into the intrigues and into Bach’s dealings with city and court, activities which probably characterized a successful life under absolute rulers – and this applied no less to Bach than to Gottsched.

Although Bach’s Mass in B minor is one of the most frequently performed works by the Cantor of St. Thomas’s, it is full of puzzles and problems. This applies not only to the question, still unanswered to this day, of why Bach composed this work, but also to many details of the musical text. That is why Carus presents the Mass in a “hybrid” version which – linked bar by bar – also presents all the relevant sources to highly revealing effect in a DVD.

Although Bach’s Mass in B minor is one of the most frequently performed works by the Cantor of St. Thomas’s, it is full of puzzles and problems. This applies not only to the question, still unanswered to this day, of why Bach composed this work, but also to many details of the musical text. That is why Carus presents the Mass in a “hybrid” version which – linked bar by bar – also presents all the relevant sources to highly revealing effect in a DVD.

In composing the Cantata BWV 149 Bach reverted to parts of an earlier work: The opening chorus is a parody of the Hunting Cantata BWV 208 (Hunting Cantata). In addition to smaller changes which were made necessary due to the text, Bach used trumpets instead of horns. For this purpose he transposed the movement from F major to C major.

In composing the Cantata BWV 149 Bach reverted to parts of an earlier work: The opening chorus is a parody of the Hunting Cantata BWV 208 (Hunting Cantata). In addition to smaller changes which were made necessary due to the text, Bach used trumpets instead of horns. For this purpose he transposed the movement from F major to C major.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!