Haydn: The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross

One Piece – Three Versions

It is rather unusual for a composer to publish his or her own work in three different versions. But that is exactly what Joseph Haydn did with his setting of Die Sieben letzten Worte unseres Erlösers am Kreuze (The Seven Last Words): The work exists in the original version for orchestra, then in an arrangement for string quartet, and – with the addition of voices and modified orchestration – in oratorio form. It would certainly not be wrong to interpret these three arrangements as a sign of the personal pride Haydn took in his composition.

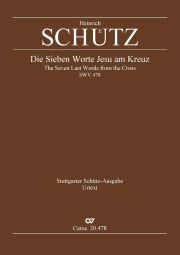

According to the Gospels, before his death on the cross Jesus uttered seven short sentences. These were compiled in the late medieval period to form a “septenary of words on the cross”; they were used as the basis of the hymn Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund (pre-1500), and, for example, the well-known composition by Heinrich Schütz (SWV 478). As well as this, around the end of the 17th century, Jesuits in Lima, Peru developed a specific Passiontide devotion based on the sayings of Jesus. This form soon reached the Catholic countries in Europe and was adapted in Spain and Italy in particular: printed devotional books describe the order of the celebration, which began around 12 noon on Good Friday and lasted until the hour of death around 3 p.m.; in this, Jesus’s words and their homiletic interpretation were framed by suitable music. Haydn’s composition belongs in this tradition, characterized by strong popular devotion.

Dr. Wolfgang Hochstein published many editions by Carus-Verlag.

The orchestral version of Die Sieben letzten Worte was written in response to a commission from Cádiz in Spain; according to this, the work was to comprise an appropriate introduction and seven instrumental movements of roughly the same length, slow yet varied, which had to reflect the respective saying of Jesus as meditative music. Haydn probably decided himself to follow the instrumental piece for the last sentence with the programmatic-theatrical word “Terremoto” (“earthquake”), thereby referring to the account in St. Matthew’s Gospel; and so the work had a rousing Finale, something which also added a considerable enrichment in terms of musical variety.

Haydn probably worked on his setting of Die Sieben letzten Worte in 1785/86. The “Introduzione”, with its striking dotted note main theme, is reminiscent of the form of the French overture, whilst this piece, like most of the following movements, is based on an individual interpretation of the sonata form. The composer developed the main themes of the text-based movements in each case “from the declamation of the biblical text” (Finscher) – a notable, unusual and new kind of artistic concept for purely instrumental music. The composition is permeated by motivic-thematic work over long stretches; contrapuntal techniques are used sparingly. The “Terremoto” ultimately does not resort to any standardised model – for plausible reasons in terms of content – but ensures that any sense of order is disrupted through much musical turbulence.

Heinrich Schütz The Seven Last Words from the Cross

Carus 20.478

The performance in Cádiz probably took place on Good Friday 1787 in Santa Cueva, a subterranean chapel. Because of the restricted space, it is not at all certain whether the arrangement for string quartet, written around the same time as the orchestral version, was played instead.

When the composer set off for his second London visit at the beginning of 1794, he stopped off in Passau where he heard a performance of his work in an arrangement by the Prince-Bishop’s Kapellmeister Joseph Friebert. Using the orchestral version as a basis, Friebert added four vocal parts and a German text to all the movements except for the “Introduzione”, which paraphrased Jesus’s words in a tone between the hymn style of the time, the melodramatic expression of Gellert’s odes and moralising exhortation. Haydn thoroughly approved of Friebert’s version; however, at the same time he was of the opinion that he could set the vocal parts better himself. Therefore, he obtained a copy of Friebert’s version, and after he had returned from London in August 1795, set about making his own vocal version. Haydn essentially took the relevant text from Friebert’s version; however, the libretto was revised by Gottfried van Swieten. In the course of this revision the “Terremoto” received a largely new text with verses by Karl Wilhelm Ramler. On 26 and 27 March 1796 the vocal version of Die Sieben letzten Worte received its premiere in the Palais Schwarzenberg in Vienna, conducted by the composer.

Oratorio de la Santa Cueva (Cádiz)

The most striking differences between the instrumental versions and the vocal version include the short unaccompanied introductions which precede most of the movements of the later composition and lend it a strange, unprecedented character. These introductions are composed in the archaic falsobordone style and are underlaid with the German translation of Jesus’s words. The 5th word “Sitio” is the only one which has no such unaccompanied introduction. Instead, Haydn included here a newly-composed second “Introduzione”: a profound piece for winds alone with distinctive contrapuntal writing.

In the 19th century, the era of flourishing choral societies, the vocal version was clearly more popular than the orchestral version, whereas in more recent times there has been much discussion of its aesthetic quality. But without doubt it is the oratorio arrangement which is most accessible to audiences. This version has just been published by Carus-Verlag in a new, critically revised edition.

Joseph Haydn The Seven Last Words of Our Saviour on the Cross

Carus 51.992

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!