Shout, up with your song

Women who write musical history

In 2017 the renowned magazine Gramophone published its list of the fifty best conductors of all time.

None of them were women.

The same list in 2023:

there were eight female conductors among the top fifty.

It’s a similar state of affairs with composers: the top 20 most frequently performed contemporary works in 2019 were all written by men. In 2022, nine women made it on the list.

In the world of pop music the situation is completely different. Here, women are at the forefront and they show everybody how it’s done. As Beyoncé proclaims, “Who run the world? Girls!”

Today the biggest pop stars in the world are women. Beyoncé, of course, and above all Taylor Swift, Adele, Rihanna, Miley Cyrus. They don’t just inspire the masses musically with their songs; they also influence politics and society. Taylor Swift supported Joe Biden in the 2020 US election. And despite – or because of – the resulting furious reaction from the Trump camp, she has become even more popular and influential since then. Beyoncé is considered an icon of feminism and uses her influence to make Black culture visible and empower Black women. And she can make a difference.

Why is it so different in the world of classical music and so-called high culture? Why is recognition so much slower here? Even female composers with extraordinary musical talent, assertiveness and visionary power are far less well known and far less often performed. There is only one positive aspect to this state of play, and that is that there‘s still so much to discover! Jewels of compositions that need to be unearthed; female composers who are definitely worth exploring; works that should be a permanent part of the concert repertoire. The life stories of the composers in the choral collection Choral Music Composed by Women often sound just as unusual as the music itself.

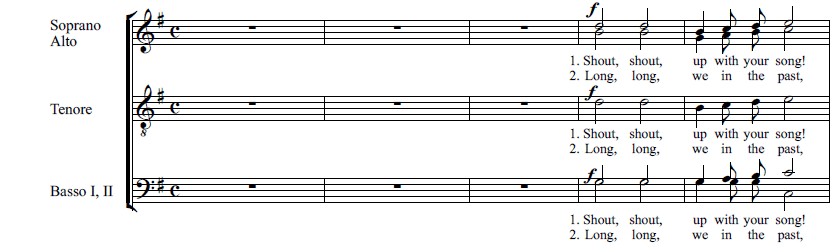

She smashed windows with the suffragettes and argued with Johannes Brahms because he didn’t think much of women composers: we’re talking about Ethel Smyth (1858–1944), of course. This British woman began her musical career with a hunger strike. It was the only way she was able to persuade her family to allow her to study composition in Leipzig from 1877. She composed choral works, symphonies, chamber music and operas. Her best-known work March of the Women (“Shout, shout, up with your song!”) became the anthem of the early English women’s rights movement. The choral setting (easy level of difficulty) can be found in Choral Music Composed by Women. Probably the most famous performance of this piece took place in 1912 in Holloway women’s prison in London, when it was sung by imprisoned women’s rights activists. The English conductor Thomas Beecham reports how the women sang in the prison yard while Smyth beat time with a toothbrush from her cell window.

Smyth received recognition and was later ennobled as a Dame of the British Empire. However after her death in 1944, she and her works were quickly forgotten. For a long time she was overshadowed by her male colleagues. It is only recently that her compositions have been rediscovered. Her determination to achieve what she set out to do and not to listen to the naysayers and pessimists is also exemplary for today’s young musicians.

March of the women

Florence Price

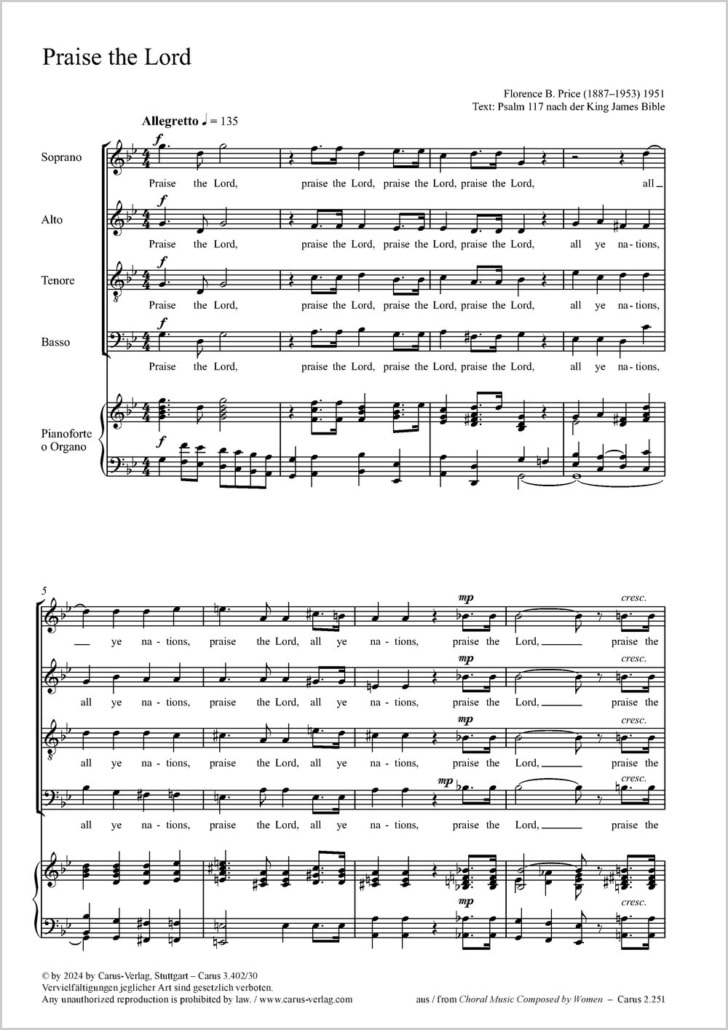

Praise the Lord

Carus 3.402/30

Florence B. Price´s (1887–1953) breakthrough as a composer came with her Symphony No. 1. This award-winning work was premiered in 1933 for the World’s Fair in Chicago. The critics were stunned, as they had not expected this from a woman – and an African-American woman at that. Nevertheless, during her lifetime Price was not awarded a place in the canon of American music history. Discrimination and prejudice in classical music were far too strong. She herself had no illusions: “I have two handicaps: I am a woman, and I have black blood in my veins,” she wrote to the chief conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1943 in an attempt to persuade him to perform her works. Without success.

The disconnect between black origins and white musical tradition was to motivate Florence Price up to her death in 1953. Her vision of uniting the music of slaves with Western music inspired the development of her own characteristic style. Pieces such as Fantasie nègre or At the Cotton Gin bear witness to this. She combined traditional orchestral instrumentation with African rhythm instruments. In addition to employing melodies from African-American folklore in her works, she also used the syncopated rhythms of “Juba” – that is, a dance which was performed by slaves who circumvented the ban on drums by stomping, clapping and body percussion. Praise the Lord (also in the new choral collection from Carus) is reminiscent of the spiritual tradition with its distinctive calls.

Florence Price could only dream that one day renowned ensembles would sing and play her music and that she would be celebrated all over the world.

Smyth and Price lived in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, times of great social upheaval. But how did women composers fare in earlier centuries, in different social and societal circumstances?

The search for clues takes us back to the seventeenth century, specifically to northern Italy around 1600. The first printed music from Venice, the music printing and publishing center of that era, reveals the names and works of a whole series of women who were highly respected musicians and composers in their time: Maddalena Casulana (c.1544–c.1590), Vittoria Aleotti (1575–after 1620), Francesca Caccini (1587–c.1640), Caterina Assandra (c.1590–1618), Chiara Margarita Cozzolani (1602–1678), Isabella Leonarda (1620-1704), Barbara Strozzi (1619–1677) and others.

Some created their works in the one environment where they could develop their compositional skills in uninterrupted safety: in a monastery. Vittoria Aleotti (1575–after 1620) grew up around the d’Este court in Ferrara as the daughter of a court architect and stage designer. As a child she already excelled at the harpsichord, just like her only slightly younger colleague Frescobaldi. At the age of 14, Vittoria Aleotti entered the San Vito convent: its reputation as a place of education and music extended far beyond the city. Under her monastic name Raffaela, Aleotti subsequently took the role of head of music in the convent, and later became the prioress. She had twenty-three female musicians, both instrumentalists and singers, at her disposal. In 1593, she had a volume of sacred motets for five to ten voices printed. That same year her father had a volume of secular madrigals published for her in Venice: this included the enchanting madrigal Hor che la vaga Aurora about the dawn and Apollo’s music, which is now included in the choral collection Choral Music Composed by Women. The convent gave Aleotti the space to develop her talent and gain a reputation as a composer far beyond its walls.

Isabella Leonarda chose a similar path in life. Born the daughter of a nobleman, she entered the Ursuline convent in Novara at the age of 16 and trained as a musician there. She published twenty collections of her own works, including instrumental pieces, which are considered to be the earliest printed instrumental compositions by a woman. She dedicated her works not only to high-ranking people such as Emperor Leopold I, but also to the Mother of God, as evidenced by the Canon coronato a 3 in the choral collection, with its sung dedication.

Maddalena Casulana and Barbara Strozzi, on the other hand, managed to lead successful careers as composers outside the monastery walls. Casulana, a celebrated singer and lutenist, is even considered to be the first woman to publish her own works. Barbara Strozzi achieved the feat of earning her living as an illegitimate daughter and later an unmarried mother of four children in Venice by singing, playing music and composing and publishing eight music collections. Both were known well beyond the borders of Italy.

Whether as successful musicians, patrons, clients, mediators, teachers or choirmasters, women have always shaped musical life. Yet as composers, they usually only had a small voice in the music scene of their time, and their works were rarely printed.

It will be interesting to see the lists of top composers, conductors, musicians in ten years‘ time. What will the rankings look like? Perhaps the Mozart of the future might even be a woman!

Dr. Barbara Mohn has been an editor at Carus-Verlag since 1994; from 2000 to 2008 she was head of the editorial section of the Rheinberger Complete Edition.

Dr. Reiner Leister is a musicologist and was a choral conductor in Aachen, Bornheim and Siegburg. As Key Account Manager at Carus-Verlag, he has been looking after choir customers worldwide since 2019.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!