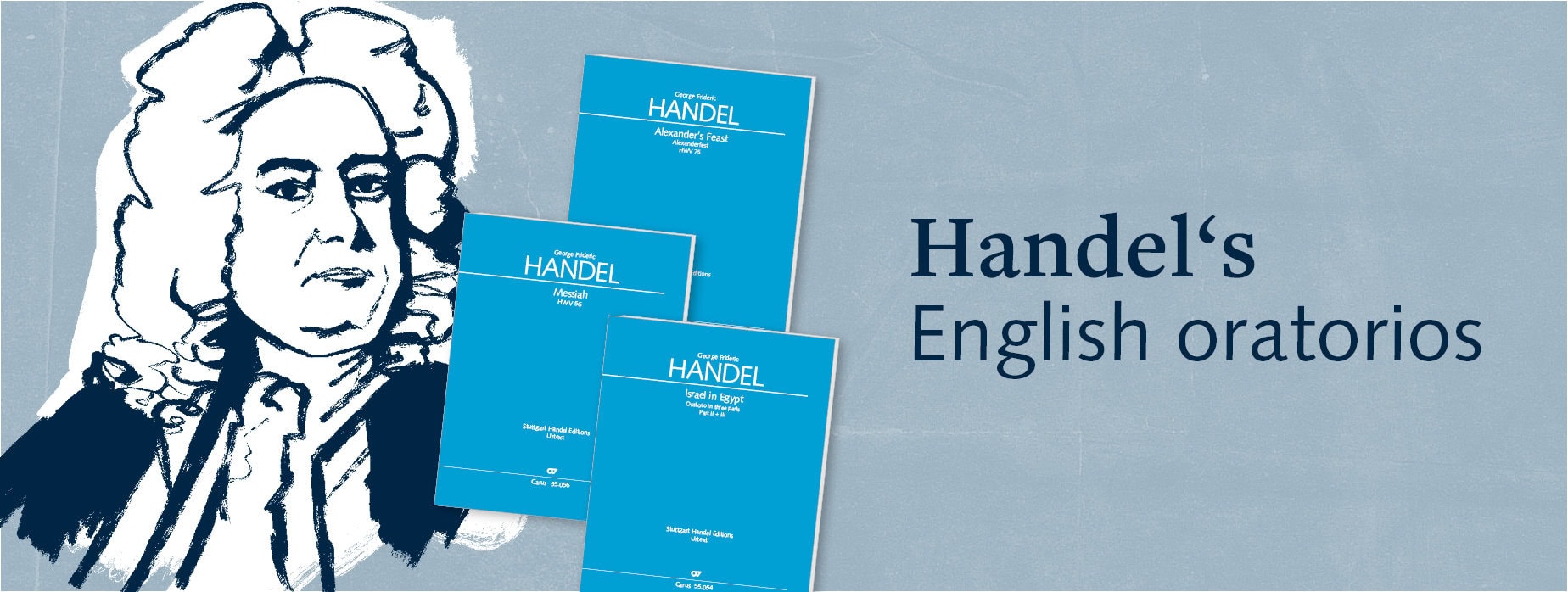

Colorful and full of emotion

Handel’s English oratorios

George Frideric Handel spent no less than two thirds of his life in England. At the age of 25, following four years’ study in Italy, he travelled to London for the first time. Just a little later he moved there for good and lived in this city, apart from travels, until the end of his life. It is therefore not surprising that his most important and greatest compositions were written in England and in the English language; these include three odes and most of his twenty-five oratorios. In this article, we are focusing in particular on works published by Carus in Urtext editions (in the original language with German translations): the ode Alexander‘s Feast, and the oratorios Israel in Egypt, Saul and Messiah.

The English oratorio can to a certain extent be described as Handel’s invention. In it, he welded together the experiences from his stay in Italy (Italian opera) with elements of the German Passion Oratorio (for example, his Brockes Passion of 1719) and the English anthem. Handel used primarily subject matter from the Old Testament, in which scenes from the story of the Israelites constitute the central focus. But he often enriched and expanded these with related dramatic and/or additional personal insertions. The libretti of Messiah and Israel in Egypt are taken almost word-for-word from the Bible and Saul also draws upon texts from the Bible. These libretti were compiled by Charles Jennens, who can probably be described as the most important of Handel’s librettists (However the libretto of Alexander’s Feast is based on an ode by John Dryden and was written by Newburgh Hamilton). Handel was less concerned with a dramatic structure for the oratorios than a portrayal of the solemn and sublime and the expression of emotions and moods (they are not, after all, operas, and a staged performance was not intended, despite minor stage instructions in some of the scores).

The period in which the above-mentioned works were written was a very fruitful phase in Handel’s creative output. He composed the ode Alexander’s Feast in 1735/36, Israel in Egypt and Saul in 1738/39, and Messiah followed in 1741/42. Furthermore, during this period he composed not only the oratorio L’Allegro, il Penseroso ed il Moderato (1740), but also a further eleven (!) operas, including what is probably his best-known, Xerxes, and – as his very last opera of all – Deidamia in 1741. It might be reasonable to assume that this intensive concentration on opera also rubbed off on the oratorios. But this is not the case at all with Messiah and Israel in Egypt. In these two oratorios Handel tells a story, describes, explains; and with tremendous stylistic sensitivity, and (as in Israel in Egypt) programmatic scenes are vividly unfolded. Messiah takes the listener on a journey into the life and Passion of Christ, allowing us to participate compassionately. The fact that divine actions underlie everything becomes clear, particularly in the great hymns of praise at the end of the oratorios. Characteristically Messiah and Israel in Egypt are the Handelian oratorios with the greatest proportion of choruses and the latter can almost be described as a chorus-oratorio. In Parts II and III alone (“Exodus” and “Moses’ Song”), the ones which are usually performed, 20 of the 31 numbers are for the chorus. The rest of the work comprises short recitatives and seven arias. Part I, the Funeral Anthem, consists entirely of numbers for chorus.

Jürgen Budday is founder and artistic director of the Maulbronn Chamber Choir. From 1979 to 2013 he was artistic director of the internationally renowned Maulbronn Monastery Concerts. He has studied Handel’s oratorios intensively and he initiated and conducted a Handel oratorio cycle from 1996 to 2009 as part of the Monastery Concerts. Recordings of the concerts are available on CD.

George Frideric Handel

Alexander’s Feast

Ode. Version of the first performance and version of 1751

Carus 55.075/00

Saul is conceived quite differently: There the chorus participates in less than a quarter of the complete work. Recitatives and arias dominate in a work which is scored for twelve (!) individual characters, therefore placing it much closer to the operatic genre. Handel makes this clear in formal terms by dividing the work into acts and scenes. Part II of the ode Alexander’s Feast (based on an ode by John Dryden) reveals its dramatic character even more strongly. As already mentioned, in all of his works Handel was less concerned with the dramatic portrayal of individual characters; he worked far more with highly differentiated musical emotions and the subtle expression of emotional states. He allows the listener to share in the emotions of the protagonists involved.

However, this requires a high degree of sensitivity from the performers regarding the expression and the rhetorical figures found in the score. There are very few dynamic indications, articulation markings are extremely sparse, and the relationship of words to music has to be discovered. But it is precisely these things which are essential for the understanding of the music, for shedding light on the plot and for the vitality of interpretations.

This will determine whether audiences simply hear the music or are gripped by it. Performers have a high degree of interpretative freedom, and, at the same time, a great responsibility to do justice to the work. A fascinating exercise and challenge for a conductor! It is impossible to embark upon a detailed study of the score here. But it is worth mentioning a few representative passages, including: several numbers in the Passion section (Part II) of Messiah, or the portrayal of the plagues in Israel in Egypt, the lament of Israel on the death of Saul and Jonathan in Saul, or the lament in Part II of Alexander‘s Feast (nos. 7 to 10). This is truly great, moving, rousing, emotional music.

And it is worth thinking about another, not entirely unproblematic aspect of performance: the question of different versions and arrangements of the oratorios. It can be assumed that these various versions are not different versions of works, but rather versions made for different performances (of a given oratorio), i.e., Handel adapted his works to suit the performance conditions in each location (the available instrumentalists, vocal soloists, quality of the choir, performance space, entertainment quality for the audience, etc.) and by doing this, tried to maximize the chances for success of a revival in each of these places.

Alexander’s Feast, alone, survives in five versions (1736, 1737, 1739, 1742, 1751). The Carus edition contains both the first version of 1736 and the last version of 1751 (Carus 55.075). The differences are not insignificant and it requires careful consideration about which one to choose as an interpreter.

There are also five versions of Messiah (1742 Dublin; 1743 London; 1745/49 London; 1750 London; 1754 the “Foundling Hospital version”). In the Carus edition all the variants are clearly listed one after another (Carus 55.056).

Alternatives which were never performed by Handel himself are found in an Appendix, so that conductors can make well-founded decisions for their own performances. Messiah and Alexander’s Feast were the oratorio and ode, respectively, which received the greatest acclaim during Handel’s lifetime. They were widely performed and secured his success and reputation. It is no coincidence that it was precisely these works which Mozart later arranged in full and clothed them with a classical orchestral garb.

Three different performance versions of the oratorio Saul were made: 1738, 1739, 1741. The Carus edition follows the first version of 1738 (Carus 55.053).

George Frideric Handel

Israel in Egypt – Part I-III

HWV 54, 1739

Carus 55.054/50

Solo: Terry Wey

Vocalensemble Rastatt · Les Favorites

Holger Speck

Carus 83.423/00

The oratorio Israel in Egypt represents a special case. Although nowadays it is mainly only Parts II (“Exodus”, the exodus of the Israelites from Egypt) and III (“Moses’ Song”, a great hymn of praise to God) which are performed, it was originally a three-part oratorio. Interestingly enough Handel composed Part III first, then Part II. Only after completing these compositions did he decide to make a three-part oratorio by placing “The Ways of Zion do mourn” first; this is the lament of the Israelites on the death of Joseph (son of the Israelite patriarch Jacob). In doing so, he drew on an earlier composition (the Funeral Anthem for Queen Caroline) which he only had to adapt slightly.

In the 1756–58 version the introductory Funeral Anthem was omitted and instead, Handel introduced sections from various other oratorios. And thus Israel in Egypt was performed in two different forms: first of all, as an oratorio in three parts, or secondly only the actual exodus from Egypt, i.e., Parts II and III. The Funeral Anthem (Part I) continues to be performed separately, as before. This is reflected in the new Carus edition; it offers not only parts I to III complete (Carus 55.054/50), but also part I (Carus 55.264), and parts II and III (Carus 55.054) as separate volumes.

In terms of scoring, Handel displayed great versatility. The orchestral scoring of Messiah can be regarded as a kind of basic scoring for Handel’s oratorios: the strings are joined by two oboes and two trumpets, plus timpani. The bass part is naturally scored for cello and bassoon.

To this basic instrumentation are added a four to five-part chorus and four soloists. With Israel in Egypt the orchestral forces are expanded by the addition of two flutes and three trombones. The chorus writing is scored for double choir for long stretches, and despite the modest amount of solo writing, six soloists are required. Alexander’s Feast is scored for rich orchestral forces: two flutes and two oboes are joined by three bassoons, two horns, two trumpets and timpani, strings with three violin parts, two viola parts, a solo cello, tutti celli and double bass all contribute to a sumptuous sound.

The chorus expands at certain points to a seven-part texture, and four soloists add to the overall musical sound. Saul is scored for even more varied forces. Twelve solo parts alone (which can be covered by six soloists) are required. The orchestra is similar to that in Israel in Egypt, but also calls for a carillon and a harp, a particular refinement to the sound.

A fundamental comment concerning the scoring of the continuo: the scoring can be varied according to the musical situation, character and emotion of a piece. This applies to whether the bass line should be played by cello or bassoon, or even by gamba and double bass or violone if necessary, and to the harmony instruments of harpsichord, organ and theorbo or lute. The greater the tonal variety and character of the instruments, the more lively the continuo part can be. This instrumental combination is the basis for each and every performance and in itself can achieve an astonishing effect alone.

Naturally the positioning of the whole ensemble influenced the sound tremendously. This did not differ inconsiderably from the practice followed in continental Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries. Hans Joachim Marx wrote about this: “In the middle of the stage (stood) the organ, and left and right of it semi-circular podiums were built up in the style of an amphitheater, on which the instrumentalists sat in raked tiers. The harpsichord probably stood in front of the organ, with the basso continuo instruments (cello, double bass, theorbo, etc.) grouped left and right. Behind this group the string and wind instruments were arranged on rostra, with the horns, trumpets, bassoons and timpani positioned on the top level. The chorus was in front of the orchestra, and at the front of the stage, separated by a balustrade, the vocal soloists sat […]. The important difference between English oratorio performances of the 18th century and continental ones of the 19th and 20th century accordingly lies in the positioning of the vocal soloists and the chorus in front of, not behind, the orchestra. In acoustic terms this results in a preference for the vocal over the instrumental, which also corresponded with the aesthetic ideas of the time…”. It is a configuration worth considering for all ensembles and concert promoters, in places where the spatial layout would allow such an alternative!

Finally, a few thoughts on performance practice. Of course, firstly every conductor has to decide whether he or she wants to perform the work with modern instruments, perhaps even in the classical-Romantic tradition, or in a historically-informed style. Convincingly performed, both these options can do justice to Handel’s music. Nevertheless, the author cannot deny that he is an avowed devotee of historically-informed performance practice. With Handel especially, an authentic performance style, if applied to all aspects of the music, gives it a more transparent, lighter sound, one which is more colorful, rhetorically catchy, vivid, tonally daring, virtuosic and, all in all, more communicative and brighter. This requires not only an instrumental ensemble specializing in these techniques, but also a chorus trained and experienced in Baroque musical practice, and soloists who are really familiar with the type of sound and the vocal and technical aspects of Baroque music (coloratura, ornamentation!). This is, however, a broad field which requires special study. Some tips on this can be found in the Carus edition of the Messiah score. There are also further references to specialist literature on Baroque performance practice.

Georg Friedrich Händel

Saul

HWV 53

Carus 83.243/00

Dresdner Kammerchor · Dresdner Barockorchester

Hans-Christoph Rademann

Carus 83.423/00

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!